01- Introduction

Problem 1

List 2 benefits of having an OS?

Instructor Solution

Here are some benefits of having an OS:

(1) Programming simplicity: OS makes programming the machine easier. Instead of seeing the hardware details, the users see abstractions such as files, directories, sockets etc.

(2) Portability: Your programs continue to run without any changes even some hardware is changed such as when you change your disk or network interface card.

(3) Efficiency: OS code is optimized for users to use the hardware in the most efficient way.

(4) Protection: OS protects different processes from interfering with each other and with the OS so that they fairly share the same hardware resources.

(5) Security: OS provides security against outsiders via authentication and intrusion detection and prevention via firewalls.

Elaboration (by LLM):

An operating system provides value by creating layers of abstraction and enforcing system-level policies:

Programming Simplicity through Abstraction:

- Without an OS, programmers would write code directly for specific hardware, which is tedious and error-prone

- The OS provides standard abstractions: files (instead of raw disk sectors), sockets (instead of network hardware details), processes (instead of CPU context)

- Example: To save data, you call

fopen()andfprintf()instead of programming disk I/O hardware manually - This vastly reduces development time and increases code maintainability

Portability and Hardware Independence:

- OS abstractions hide hardware differences from applications

- A program written for Linux can be recompiled and run on Windows because both OSs provide similar abstractions (files, system calls, memory)

- When you upgrade your hard drive or network card, existing programs continue to work without modification because the OS driver layer handles hardware differences

- This allows software to have a longer lifespan and reach broader markets

Efficiency and Resource Optimization:

- OS engineers optimize code for CPU scheduling, memory management, and I/O handling

- Individual programmers would likely write inefficient code if they managed these resources directly

- OS techniques like caching, prefetching, and CPU scheduling maximize hardware utilization

Protection and Security:

- OS enforces privilege separation: user processes cannot directly access hardware or crash the system

- Memory protection prevents one process from corrupting another’s data

- Authentication and firewalls prevent unauthorized access to the system

Without an OS, every programmer would need to be a hardware expert, programs would be hardware-specific, and system stability would be impossible to guarantee.

Problem 2

How does an OS provide I/O device independence to application programs?

Instructor Solution

An OS provides I/O device independence by implementing a layer of abstraction between the application and the hardware, typically through a standardized System Call API. Instead of writing code to communicate with the specific electrical signals of a particular hard drive or network interface card, applications use generic system calls like read() or write(). The OS maps these calls to device drivers, which are specialized software modules that translate the generic requests into the specific commands required by the actual hardware. By decoupling the high-level logic from the low-level hardware details, the OS allows the same application to run on various hardware configurations without needing to be modified or recompiled.

Elaboration (by LLM):

I/O device independence is one of the most valuable abstractions an OS provides:

The Problem Without Abstraction:

- Without an OS, each program would need to know the exact electrical protocol and registers for every device

- A

read()operation would require completely different code for a SATA disk vs. an NVMe drive - Programs would be tied to specific hardware manufacturers

- Adding new hardware would require rewriting application code

How the OS Solves This:

Standard API:

- Applications use generic system calls:

read(fd, buffer, count)andwrite(fd, buffer, count) - These calls don’t mention specific hardware; they just specify what the program needs

- The same application code works on any hardware the OS supports

Device Drivers:

- OS vendors write device drivers for each supported device

- A device driver is a kernel module that translates

read()/write()into device-specific commands - When a new disk model comes out, the vendor releases a driver; applications work without changes

Virtual File System (VFS):

- Linux/Unix uses a unified VFS layer above all devices

- All devices appear as files in

/dev/:/dev/sda(disk),/dev/eth0(network),/dev/tty(terminal) - Applications read from any device the same way:

read(fd, buffer, 512)

Example:

// Same code works for disk, network, USB, etc.

int fd = open("/dev/sda", O_RDONLY);

read(fd, buffer, 512); // Works for ANY storage deviceBenefit: Application vendors only write code once; users can run the same binary on computers with different hardware configurations.

Problem 3

Briefly explain how polling-based I/O works.

Instructor Solution

In polling-based I/O, also known as programmed I/O, the CPU takes an active role in monitoring the status of a hardware device by repeatedly reading its status register in a loop. When the CPU needs to perform an I/O operation, it issues the command and then enters a “busy-wait” state, continuously “asking” the device if it has completed the task or is ready to receive more data. Because the CPU cannot move on to other instructions until the device bit changes state, this method is highly inefficient for slow devices, as it consumes 100% of the CPU’s cycles on a single task and prevents any meaningful CPU-I/O overlap.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Polling is a simple but inefficient approach to I/O:

Basic Mechanism:

- CPU issues an I/O command to device

- CPU enters a loop, repeatedly checking the device’s status register

- On each iteration, CPU reads: “Is the operation done yet?”

- Once device sets a status bit indicating completion, CPU reads the data and continues

Why It’s Inefficient:

- Wasted CPU Cycles: The CPU spins in a loop doing nothing productive while the device operates

- No CPU-I/O Overlap: CPU is blocked; it cannot do other useful work

- Busy-Wait: The CPU consumes 100% power and generates heat checking a device that’s probably not ready

- Terrible Scaling: Reading from a slow disk might waste thousands of CPU cycles

Example:

// Polling: CPU wastes cycles checking this

status = read_device_status_register();

while ((status & DONE_BIT) == 0) {

status = read_device_status_register(); // Check again...

}

data = read_device_data(); // Finally!When It’s Used:

- Modern systems rarely use polling for I/O

- Exception: real-time systems where predictability matters more than efficiency

- High-performance networking sometimes polls instead of using interrupts (NAPI in Linux)

Comparison: Interrupt-driven I/O is far superior because the CPU can do other work while the device operates.

Problem 4

Briefly explain how interrupt-driven I/O works.

Instructor Solution

In interrupt-driven I/O, the CPU issues an I/O command to a device and then immediately moves on to other tasks rather than waiting for a response. The hardware device works independently and, once it has finished the operation or is ready for the next data transfer, it triggers a hardware signal called an interrupt to notify the CPU. Upon receiving this signal, the CPU temporarily suspends its current process, executes an interrupt handler in the kernel to manage the I/O data, and then resumes its previous work. This approach eliminates “busy-waiting,” enabling CPU-I/O overlap and allowing the operating system to maintain high efficiency by running other programs while the I/O operation is in progress.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Interrupt-driven I/O is the modern standard approach that enables CPU-I/O overlap:

Basic Mechanism:

- CPU issues an I/O command to device

- CPU immediately returns to executing other instructions (does NOT wait)

- Device operates independently in the background

- Once device completes the operation, it raises an interrupt signal

- CPU stops whatever it’s doing, handles the interrupt (reads data), and resumes

Key Advantage: CPU-I/O Overlap

Instead of one task blocking while I/O completes, the scheduler can run other processes:

Time CPU Activity Disk Activity

0-100µs: Process A (I/O call) Disk idle

100-1000µs: Process B running Disk reading ← overlap!

1000µs: Interrupt from disk Disk done

Kernel saves ProcessA

ProcessA continues

The disk works while other processes use the CPU—massive efficiency gain.

Interrupt Handler:

When the interrupt fires, the kernel:

- Saves current process state (context switch to kernel)

- Executes interrupt handler (moves data from device to memory)

- Wakes up waiting process (moves to ready queue)

- Returns to whatever was running

Why It’s Better Than Polling:

- CPU doesn’t waste cycles checking device status

- Multiple I/O operations can overlap

- System can run more processes in parallel

- Power consumption is lower (CPU can sleep while waiting)

Cost: Small overhead of context switching and interrupt handling, but far outweighed by efficiency gains.

Problem 5

What is Direct Memory Access (DMA) and briefly explain how it works and why it is useful?

Instructor Solution

Direct Memory Access (DMA) is a specialized hardware feature that allows I/O devices to transfer large blocks of data directly to or from main memory without continuous intervention from the CPU. Instead of the CPU moving data byte-by-byte (which would happen in standard interrupt-driven I/O), the CPU simply gives the DMA controller the starting memory address and the total number of bytes to transfer, then moves on to other work. Once the transfer is complete, the DMA controller sends a single interrupt to the CPU to signal that the data is ready. This is incredibly useful because it prevents the CPU from being “bogged down” by high-speed data transfers—such as those from disk drives or network cards—significantly increasing overall system performance and throughput.

Elaboration (by LLM):

DMA is a specialized hardware subsystem that further optimizes I/O by completely removing the CPU from data movement:

Problem Without DMA:

In interrupt-driven I/O without DMA, even though the CPU doesn’t poll, it still handles every data byte:

- CPU initiates disk read

- Device finishes reading one chunk (e.g., 512 bytes)

- Device interrupts CPU

- CPU must transfer all 512 bytes from device buffer to memory

- Device finishes next chunk

- CPU interrupts again and transfers 512 more bytes

- Repeat thousands of times…

For high-speed devices (network: gigabits/sec), this becomes a bottleneck.

How DMA Works:

-

Setup: CPU tells DMA controller:

- Starting memory address (where to put data)

- Number of bytes to transfer

- Device to read from

-

Transfer: DMA controller takes over the data bus and moves bytes directly from device to memory (CPU not involved)

-

Completion: When done, DMA controller sends a single interrupt to CPU

Example:

// CPU says "transfer 1MB from disk to memory"

dma_setup(disk_device, memory_addr, 1MB);

// CPU continues doing other work

process_network_packets();

// 10ms later: interrupt says "transfer done"

handle_dma_interrupt(); // Data is already in memory!Why It’s Useful:

- CPU Freed Up: CPU can do real work instead of moving data

- Single Interrupt: One interrupt for 1MB instead of thousands for smaller chunks

- Bus Utilization: DMA doesn’t compete with CPU for memory bus access (has its own)

- High-Throughput I/O: Makes gigabit networks and fast SSDs practical

Real-World Impact:

Without DMA, a gigabit network card transferring 125 MB/sec would consume nearly 100% of a modern CPU just moving bytes. DMA reduces this to < 1%.

Problem 6

What is the primary purpose of an Interrupt Request (IRQ)?

Instructor Solution

To signal the CPU that a hardware device needs immediate attention. An IRQ is the electrical or logical signal used by hardware to pause the CPU’s current task to handle a time-sensitive event such as the pressing of a key, the completion of a disk read, or the arrival of a network packet.

Elaboration (by LLM):

An IRQ is the fundamental mechanism that enables hardware devices to grab the CPU’s attention:

What Is an IRQ?

- An IRQ (Interrupt Request) is an electrical signal on dedicated hardware lines that devices use to notify the CPU

- Each device or type of event has its own IRQ number (IRQ0 for timer, IRQ1 for keyboard, etc.)

- In modern systems, IRQs can be routed through an interrupt controller (PIC or APIC) to manage priorities

Why IRQs Are Essential:

Without IRQs, the CPU would have to continuously poll every device (“Is keyboard ready? Is disk ready? Is network packet here?”), which would be extremely inefficient.

IRQ vs. Polling:

| Method | Who Initiates? | CPU Overhead | Response Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polling | CPU checks device | High | Slow |

| IRQ | Device notifies CPU | Low | Fast |

Example Timeline with IRQ:

Time 0: CPU running Process A

Time 5: User presses keyboard key

Time 6: Keyboard device raises IRQ1

Time 7: CPU pauses Process A

CPU jumps to keyboard interrupt handler

Interrupt handler reads keyboard

Interrupt handler queues keystroke

Time 8: CPU resumes Process A

The CPU didn’t waste time checking the keyboard; the keyboard device told the CPU when it had data.

Types of Events That Trigger IRQs:

- Timer tick (preemptive multitasking)

- Keyboard/mouse input

- Disk I/O completion

- Network packet arrival

- Hardware error (parity error, etc.)

Priority: Some IRQs are higher priority than others. A hardware error might have higher priority than a keyboard interrupt.

Problem 7

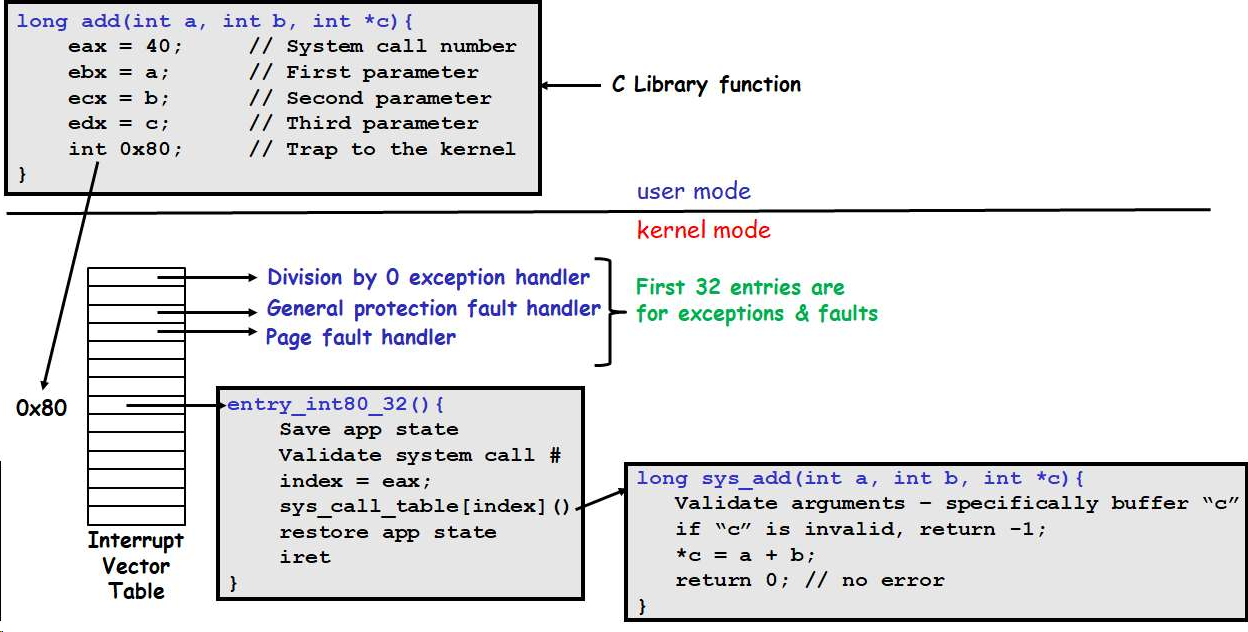

What is the Interrupt Vector Table (IVT) or Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT)?

Instructor Solution

The IVT is an array of function pointers and acts as a lookup directory where the CPU finds the entry point for the code (the interrupt service routine ISR) needed to handle a specific interrupt.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The IVT/IDT is a critical kernel data structure that directs interrupt handling:

Definition:

The Interrupt Vector Table (IVT) or Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) is an array of entries in kernel memory where each entry corresponds to a different interrupt type or IRQ number.

Structure:

Each entry in the IVT contains:

- Address of ISR: The kernel address where the interrupt handler routine lives

- Privilege Level: Whether the handler runs in kernel or user mode

- Gate Type: Whether it’s an interrupt gate, trap gate, or task gate

How It Works:

- CPU receives an interrupt (IRQ5 from disk)

- CPU looks up entry 5 in the IVT

- Entry 5 contains the address of the disk interrupt handler

- CPU jumps to that address and executes the handler

IVT in Memory:

Entry 0: Address of Divide-by-Zero handler

Entry 1: Address of Debug handler

Entry 2: Address of NMI handler

...

Entry 5: Address of Disk I/O handler ← IRQ5 points here

...

Entry 32: Address of Timer handler

...

Why It’s Necessary:

- Flexible: Different ISRs can be installed at different addresses

- Fast: CPU looks up handler address in O(1) time

- Multiplex: Single hardware line (e.g., PCI shared IRQ) can be handled by kernel code that dispatches to the correct driver

- Protected: Only kernel can modify the IVT (prevents user code from hijacking interrupts)

Size: x86 systems typically support 256 interrupt vectors (0-255). Entries 0-31 are reserved for CPU exceptions (divide-by-zero, page faults, etc.); 32+ are for external IRQs.

Real System: In Linux, the IVT is called the IDT (Interrupt Descriptor Table) and is set up early in the boot process.

Problem 8

What is an Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) and who is responsible for writing it?

Instructor Solution

ISRs are software functions found within device drivers that define exactly how the OS should interact with the hardware. They are implemented by the device driver developers.

Elaboration (by LLM):

An ISR is the actual handler code that executes when an interrupt fires:

Definition:

An Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) is a kernel function that executes in response to a hardware interrupt. It contains the code that handles the specific interrupt event.

Typical ISR Responsibilities:

- Acknowledge the Device: Tell the device “I received your interrupt”

- Read Data: If applicable, read data from device buffer (e.g., keyboard input, network packet)

- Handle Error: Check for error conditions

- Update Kernel Data Structures: Wake up a process, queue data, etc.

- Return Control: Return from interrupt so interrupted code can resume

Example (Simplified Keyboard ISR):

void keyboard_isr() {

// 1. Acknowledge interrupt to keyboard controller

outb(0x20, 0x61);

// 2. Read which key was pressed

int keycode = inb(0x60);

// 3. Convert keycode to ASCII

char ascii = keycode_to_ascii(keycode);

// 4. Add to keyboard buffer

keyboard_buffer[buffer_head++] = ascii;

// 5. Wake up any process waiting for keyboard input

wake_process(waiting_for_keyboard);

}Who Writes ISRs:

Device driver developers write ISRs because they must understand the specific hardware protocol:

- Keyboard protocol (what registers mean what)

- Disk controller protocol (what commands to send)

- Network card protocol (how to read packet data)

- Etc.

The OS vendor (Linux, Microsoft) sometimes provides ISRs for common devices; third-party vendors write ISRs for specialized hardware.

ISR Constraints:

- Fast: ISRs must complete quickly (blocking other interrupts)

- Minimal: Do only essential work (move data, acknowledge device)

- Careful: ISRs run in kernel mode with full privileges

- No Blocking: Cannot call sleeping functions (mutexes, disk I/O)

- No User Access: Cannot call user-space functions (would crash!)

Deferred Work: For heavy processing, ISRs often queue work for a kernel thread to handle later (bottom-half handling in Linux).

Problem 9

When a CPU receives an IRQ, what is the very first thing it must do before jumping to the ISR?

Instructor Solution

Save the current state (registers/flags) onto the stack so it can resume exactly where it left off once the interrupt is finished.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Saving state is essential for resuming the interrupted process correctly:

Why Saving State Is Critical:

Without saving the interrupted process’s state, the CPU would have no way to resume it. The ISR will use CPU registers and modify flags; if these aren’t saved first, the interrupted process would resume with corrupted state.

What Must Be Saved?

The CPU automatically saves:

- Program Counter (EIP/RIP): Address of the instruction being executed when interrupt arrived

- Processor Flags (EFLAGS): Status flags like Zero flag, Carry flag, etc.

- Code Segment Selector: Privilege level, segment information

Some systems also save:

- General-Purpose Registers: EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX, ESI, EDI, EBP (saved by ISR or CPU)

- Stack Pointer: ESP (if privilege level changes from user to kernel)

When Does It Happen?

The CPU hardware automatically saves EIP and EFLAGS when an interrupt occurs—this is done by the CPU’s interrupt handling circuitry, not software.

Additional registers are saved by the ISR code using PUSH instructions.

Where Is It Saved?

The saved state is pushed onto the kernel stack (or interrupted process’s stack if already in kernel).

Visual Timeline:

Time T: CPU executing Process A at address 0x1000

Instruction: ADD EAX, EBX

Flags: ZF=0, CF=1, ...

IRQ5 fires (disk interrupt)

CPU Hardware Action:

- PUSH EIP (0x1000)

- PUSH EFLAGS (ZF=0, CF=1, ...)

CPU jumps to ISR address from IVT

ISR: PUSH EBX ; Save more registers

PUSH ECX

... handle interrupt ...

POP ECX

POP EBX

IRET ; Pops EIP and EFLAGS, resumes at 0x1000

Time T+ε: Process A resumes at 0x1000

All registers and flags restored exactly as they were

IRET Instruction:

The IRET (Interrupt Return) instruction reverses this:

- Pops EIP from stack

- Pops EFLAGS from stack

- Resumes execution at the saved address with saved flags

Without saving state first, the interrupted process would be corrupted irreversibly.

Problem 10

What instruction is typically used at the end of an ISR to return the CPU to its previous task?

Instructor Solution

IRET is specifically designed to pop the saved flags and instruction pointer off the stack to resume the interrupted process.

Elaboration (by LLM):

IRET (Interrupt Return) is a special CPU instruction that reverses the interrupt mechanism:

What IRET Does:

The IRET instruction performs these steps atomically:

- Pop EIP (or RIP in 64-bit): Restores the program counter to where the interrupt occurred

- Pop EFLAGS (or RFLAGS): Restores processor flags to their saved state

- Pop CS (Code Segment): Restores the code segment (privilege level may change)

- Resume Execution: CPU continues executing at the restored EIP

Why Not Just RET?

A regular RET instruction only pops the return address (EIP); it doesn’t restore EFLAGS or handle privilege level changes. If an interrupt occurred in user mode, a simple RET would leave the CPU in kernel mode—a catastrophic security hole.

Atomic Operation:

IRET is atomic—the CPU executes it as a single indivisible unit. This is critical because:

- Switching privilege levels mid-instruction would be unsafe

- Flags must be restored together with EIP for correct semantics

Simplified ISR with IRET:

// In assembly

keyboard_isr:

PUSH EBX ; Save additional registers

PUSH ECX

// ... handle interrupt ...

MOV AL, [0x60] ; Read keyboard data

MOV [buffer], AL ; Store in buffer

POP ECX ; Restore registers

POP EBX

IRET ; Restore EIP, EFLAGS, privilege level

; Resume interrupted processPrivilege Level Change:

If the interrupt occurred while the CPU was in user mode (privilege level 3), IRET automatically switches back to user mode. The saved CS register contains the privilege level information.

Comparison with System Call Return:

- Interrupt: Use

IRETto restore both EIP and EFLAGS - System Call: May use

SYSRET/SYSEXITorIRETdepending on how the call was made

The key difference: Interrupts save EFLAGS, so IRET is needed to restore them properly.

Problem 11

Why are the first 32 entries in the x86 IVT/IDT reserved?

Instructor Solution

They are reserved for CPU-internal exceptions like ‘Divide by Zero’ or ‘Page Faults’.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The first 32 entries are reserved for CPU-generated exceptions, not device interrupts:

CPU Exceptions (Entries 0-31):

These are synchronous events generated by the CPU itself during execution, not external devices:

| Entry | Exception | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Divide by Zero | DIV/IDIV by zero |

| 1 | Debug | Debugger breakpoint (INT 1) |

| 2 | NMI (Non-Maskable) | Unmaskable interrupt (hardware error) |

| 3 | Breakpoint | INT 3 instruction (debugger) |

| 4 | Overflow | INTO instruction when overflow flag set |

| 5 | Bound Range Exceeded | BOUND instruction violation |

| 6 | Invalid Opcode | Unknown CPU instruction |

| 7 | Device Not Available | Floating-point unit unavailable |

| 8 | Double Fault | Exception during exception handling |

| 10 | Invalid TSS | Bad Task State Segment (x86 multitasking) |

| 11 | Segment Not Present | Invalid segment descriptor |

| 12 | Stack-Segment Fault | Stack segment violation |

| 13 | General Protection | Privileged instruction in user mode |

| 14 | Page Fault | Invalid memory access |

| 16 | Floating-Point | FPU error |

| 17 | Alignment Check | Unaligned memory access |

| 18 | Machine Check | Hardware failure detected |

Why Reserved?

- Standardization: Intel/AMD defined these for all x86 systems—uniform across all machines

- Essential: The CPU cannot function without handlers for these exceptions

- Internal: Generated by CPU logic, not external devices

- Priority: Many are critical (page fault, general protection fault)

External IRQs Start at Entry 32:

Entries 32-255 are available for device interrupts:

- IRQ0 (timer) → Entry 32

- IRQ1 (keyboard) → Entry 33

- IRQ3-15 → Entries 35-47

- IRQ32+ (modern APIC) → Entries 48+

Why This Matters for Programmers:

When you write a kernel or device driver:

- Never put device handlers in entries 0-31

- Always use entries 32+ for IRQ handlers

- Respect the Intel standard so your code works on any x86 system

Example Kernel Initialization Code:

// Set up CPU exception handlers (entries 0-31)

set_exception_handler(0, divide_by_zero_handler);

set_exception_handler(8, double_fault_handler);

set_exception_handler(14, page_fault_handler);

// Set up device interrupt handlers (entries 32+)

set_irq_handler(32, timer_handler); // IRQ0

set_irq_handler(33, keyboard_handler); // IRQ1Problem 12

Briefly summarize the relationship between IRQ, IVT, and ISR.

Instructor Solution

IRQ is the interrupt signal or number, IVT is the directory, an array of function pointers to the functions that will handle the interrupt, and ISR is the handler code. This correctly identifies the trigger, the lookup mechanism, and the resulting action.

Elaboration (by LLM):

These three concepts form the foundation of interrupt-driven I/O:

The Flow:

Device Event (e.g., keyboard press)

↓

IRQ Signal (electrical signal from device)

↓

CPU receives IRQ, looks up entry in IVT

↓

IVT directs CPU to ISR address

↓

CPU executes ISR code

↓

ISR handles event (reads data, wakes process)

↓

IRET returns control to interrupted code

IRQ (Interrupt ReQuest):

- Definition: The signal that initiates the entire interrupt sequence

- Source: Hardware device (keyboard, disk, timer, network card)

- Nature: Electrical signal on dedicated hardware line

- Numbering: IRQ0 = timer, IRQ1 = keyboard, IRQ4 = serial port, etc.

- Role: “Hey CPU, something happened that needs your attention!”

IVT (Interrupt Vector Table):

- Definition: Kernel data structure (array of entries)

- Location: In kernel memory (fixed address known to CPU)

- Content: Each entry contains the memory address of an ISR

- Indexing: Entry number = IRQ number (mostly)

- Role: “For IRQ5, go execute the code at address 0xC0001000”

- Protection: Kernel-only; user code cannot modify

ISR (Interrupt Service Routine):

- Definition: The actual kernel function that handles the interrupt

- Written by: Device driver developers

- Executes in: Kernel mode with full privileges

- Responsibility: Read device data, process it, wake processes, acknowledge device

- Duration: Very short (microseconds to milliseconds)

- Role: “Okay, the keyboard sent IRQ1. Let me read which key was pressed and queue it.”

Concrete Example:

User presses 'A' key

Hardware detects keystroke

↓

Keyboard controller raises IRQ1

CPU stops running Process B

Saves Process B's state

↓

CPU looks up IVT[1]

↓

IVT[1] contains: 0xC0005000

↓

CPU jumps to 0xC0005000 (keyboard_isr function)

↓

keyboard_isr() {

data = read_keyboard_port(); // Gets 'A'

queue_char('A'); // Adds to buffer

wake_process(waiting_shell); // Wakes shell

}

↓

keyboard_isr returns (IRET)

↓

Process B resumes exactly where it left off

Summary Table:

| Concept | Role | Key Property |

|---|---|---|

| IRQ | Signal | External, asynchronous |

| IVT | Lookup table | Kernel memory, fixed |

| ISR | Handler code | Kernel function |

Without all three:

- No IRQ → devices can’t notify CPU

- No IVT → CPU doesn’t know which code to run

- No ISR → no code to handle the event

Problem 13

What are the major components of an operating system? Briefly explain their responsibilities.

Instructor Solution

(1) Process Manager: Deals with the creation, scheduling, synchronization of the processes running in the system.

(2) Memory Manager: Deals with the allocation, deallocation and protection of RAM to active processes in the system.

(3) I/O Manager: Deals with managing both the physical hardware—like disks, keyboards, and network cards—and the logical organization of data into files and directories. It abstracts the complexities of the hardware, providing a uniform interface (like a file descriptor) that allows processes to read from or write to a disk just as easily as they would a network socket or a terminal.

Elaboration (by LLM):

These three subsystems are the pillars of every operating system:

Process Manager (Scheduler & Dispatcher):

Responsibilities:

- Creation:

fork(),CreateProcess()to spawn new processes - Scheduling: Decide which process runs next (round-robin, priority-based, etc.)

- Context Switching: Save/restore process state during preemption

- Synchronization: Mutexes, semaphores to coordinate multiple processes

- Termination: Handle

exit()andkill, reap zombie processes

Key Operations:

Process Manager maintains: {ready_queue, blocked_queue}

Timer interrupt fires every 10ms → run scheduler

Scheduler picks next process → run dispatcher

Dispatcher loads process state → resume execution

Memory Manager (Virtual Memory):

Responsibilities:

- Allocation:

malloc(), page allocation for heap/stack - Deallocation:

free(), page reclamation - Protection: Enforce memory boundaries (one process cannot read another’s memory)

- Virtual Memory: Page tables, paging, swapping to disk

- Fragmentation: Manage unused memory, compaction

Key Operations:

Process requests memory: malloc(1000)

Memory Manager finds free page frame

Allocates to process

Marks page as "in use"

If no free frames: evict least-used page to disk

I/O Manager (Device Management & File System):

Responsibilities:

- Device Drivers: Manage specific hardware (disk controllers, network cards)

- File System: Provide files and directories (logical abstraction)

- Buffering: Cache frequently accessed data in memory

- Interrupt Handling: Manage IRQs from I/O devices

- Resource Allocation: Assign disk bandwidth, network bandwidth, etc.

Key Operations:

User calls: read("file.txt")

I/O Manager translates to disk block locations

Initiates disk read (interrupt-driven)

Device reads data

Interrupt fires → I/O Manager moves data to user buffer

User process wakes up with data ready

Interactions Between Subsystems:

Process Manager Memory Manager I/O Manager

| | |

| fork() | |

+──────→ needs memory ────→| |

| | |

| malloc() | |

+──────────────────────→ | |

| | |

| open("file.txt") | |

+──────────────────────────────────────────────→ |

| | |

| read() blocks | ← I/O interrupt |

| | wakes up process |

Real-World Example:

When you run cat file.txt:

- Process Manager: Creates new process, schedules it

- Memory Manager: Allocates memory for the process

- I/O Manager: Opens the file, reads disk blocks

- Process Manager: Blocks cat process while waiting for disk

- I/O Manager: Disk interrupt fires, wakes process

- Memory Manager: Ensures output buffer is accessible

- Process Manager: Schedules cat to run again with data ready

All three subsystems work together seamlessly.

Problem 14

Briefly explain what’s multi-tasking and what is the main motivation for it? Is Linux a multi-tasking OS? Why or why not?

Instructor Solution

Multi-tasking is an operating system’s ability to keep multiple processes in memory and execute them concurrently by rapidly switching the CPU among them. The primary motivation is to maximize CPU utilization; by scheduling a new task whenever the current one is waiting for I/O or an external event, the OS ensures the processor remains busy rather than sitting idle. Linux is a multi-tasking OS because its kernel uses a sophisticated scheduler to manage thousands of processes, giving each a “time slice” so they appear to run simultaneously to the user.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Multi-tasking is a fundamental feature of modern operating systems:

Definition:

Multi-tasking is the OS’s ability to manage multiple processes in memory and execute them concurrently by rapidly switching the CPU among them. At any instant, only one process is executing (on single-core systems), but the OS rotates through processes so quickly that they appear simultaneous to the user.

Motivation: CPU Utilization

Without multi-tasking:

Time 0-100ms: Process A reads from disk (CPU idle)

Time 100-200ms: CPU finally has data, Process A runs

Time 200-300ms: Process A writes to network (CPU idle)

CPU sits idle 66% of the time!

With multi-tasking:

Time 0-100ms: Process A issues disk read

Time 0-10ms: Process B runs

Time 10-20ms: Process C runs

Time 20-30ms: Process D runs

...

Time 100ms: Disk interrupt! Wake Process A

Time 100-110ms: Process A continues

CPU never sits idle—processes run while others wait for I/O.

How Multi-tasking Works:

- Timer Interrupt: Hardware timer fires every 10ms (adjustable)

- Context Switch: OS saves current process state, loads next process

- CPU-I/O Overlap: While one process waits for I/O, others use CPU

- Fairness: Scheduler ensures all processes get CPU time

Throughput Improvement:

Multi-tasking can increase utilization from ~30% (single-task) to ~90% (multi-task).

Is Linux Multi-tasking?

Yes, absolutely. Linux is a multi-tasking OS because:

- Multiple Processes: Can have thousands of processes running simultaneously

- Sophisticated Scheduler: The Linux kernel (CFS—Completely Fair Scheduler) manages process scheduling

- Time Slices: Each process gets a small quantum (typically 1-100ms)

- Concurrent Execution: Processes appear to run in parallel even on single-core CPUs

- Process States: Kernel tracks ready, running, and blocked queues

Example:

$ cat /proc/stat # Check CPU utilization

$ ps aux # List thousands of processes

$ top # Watch processes switch in real-timeEven on a single-core CPU, Linux efficiently multi-tasks 100+ processes.

Related Concepts:

- Multi-processing: Multiple independent processes (✅ Linux supports this)

- Multi-threading: Multiple threads within one process (✅ Linux supports this)

- Time-sharing: Same as multi-tasking in most contexts (✅ Linux does this)

- Preemptive Multitasking: OS forces process off CPU (✅ Linux does this)

Without multi-tasking, you could only run one program at a time—no background processes, no parallel compilation, no web server handling multiple clients. Modern systems would be unusable.

Problem 15

Briefly explain when you will use a timesharing OS? Is Windows a timesharing OS?

Instructor Solution

A timesharing OS is one that divides the time into slices and allocates each task a time slice or quantum of CPU time creating the illusion that each task has exclusive access to hardware resources. The goal is to minimize response time. Windows is a timesharing OS because its scheduler uses preemptive multitasking to distribute processor time among competing threads; this prevents any single application from monopolizing the CPU and ensures the system remains responsive to user input.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Timesharing is a specialized scheduling strategy for interactive systems:

Definition:

Timesharing is an OS design where CPU time is divided into small slices (quanta, typically 1-100ms), and each process/user gets a small quantum in round-robin fashion. The goal is to minimize response time—how quickly a user sees feedback.

When to Use Timesharing OS:

Interactive Systems:

- Desktop computers (Ubuntu, Windows, macOS)

- Workstations where users expect quick response

- Servers handling multiple interactive users

- Mobile devices (Android, iOS)

Not for:

- High-throughput batch systems (maximize CPU utilization instead)

- Embedded real-time systems (minimize latency, not response time)

- Scientific computing farms (maximize parallel execution)

Timesharing vs. Multi-tasking:

| Feature | Multi-tasking | Timesharing |

|---|---|---|

| Processes | Multiple processes OK | Multiple processes required |

| Goal | Maximize CPU utilization | Minimize response time |

| Context Switch | When I/O or on timer | Regularly on timer (frequent) |

| Time Quantum | Long or variable | Fixed, small (10-100ms) |

| User Interaction | Batch-oriented | Interactive, real-time |

How Timesharing Works:

Scheduler with 4 processes (A, B, C, D)

Time quantum = 10ms

Time 0-10ms: Process A runs (quantum expires)

Save A's state → Load B's state

Time 10-20ms: Process B runs

Save B's state → Load C's state

Time 20-30ms: Process C runs

Save C's state → Load D's state

Time 30-40ms: Process D runs

Save D's state → Load A's state

Time 40-50ms: Process A runs again

Each process gets CPU time regularly, creating the illusion of simultaneous execution.

Is Windows a Timesharing OS?

Yes. Windows is a timesharing OS because:

- Preemptive Multitasking: Timer interrupt forces CPU to switch processes every ~20ms

- Response Time Focus: Desktop apps remain responsive even when other programs run

- Fair Scheduling: Windows scheduler distributes CPU time in small quanta

- Thread-Based: Windows uses threads that time-share CPU cores

Example:

When you:

- Run a slow file copy in the background

- Open a new application

- Click a window

The OS interrupts the file copy process every 20ms, giving other processes a turn. This is why your desktop stays responsive even during heavy background tasks.

Timesharing Overhead:

Frequent context switching has a cost:

- Saving/restoring process state: ~1µs per switch

- TLB/cache misses due to process switching

- 40 switches/sec × 1µs = 0.04% overhead (acceptable)

For comparison, a high-throughput batch system might switch only once per second to minimize overhead.

Modern Timesharing Variations:

Completely Fair Scheduler (Linux CFS):

- Processes get CPU time proportional to priority

- No fixed time quantum; more sophisticated

Priority-Based (Windows):

- Higher-priority processes get longer quanta

- Interactive processes get priority boost

Multilevel Feedback Queues:

- Different queues for different process types

- Adaptive quanta based on behavior

Timesharing is why your personal computer feels responsive—the OS ensures every process gets regular attention.

Problem 16

What’s a timer interrupt? What is it used for in modern timesharing OSs?

Instructor Solution

A timer interrupt is a hardware-generated signal produced by a dedicated physical clock (the system timer) that periodically pauses the CPU’s current execution and transfers control to the operating system’s kernel. In modern timesharing operating systems, this interrupt is the fundamental mechanism used to implement preemptive multitasking. Each process is assigned a small “time slice” or quantum; when the timer interrupt fires, the OS scheduler regains control to check if the current process has exhausted its slice. If it has, the OS performs a context switch, saving the state of the current process and loading the next one. This ensures that no single program can monopolize the CPU, maintaining system responsiveness and providing the illusion that multiple applications are running simultaneously.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Timer interrupts are the heartbeat of preemptive multitasking:

Hardware Timer:

- Dedicated hardware clock on the motherboard (programmable interval timer)

- Generates an electrical signal at regular intervals (e.g., every 10ms, 100Hz)

- Signal is wired to CPU as a hardware interrupt (IRQ0 on x86)

- Independent of CPU execution; fires regardless of what the CPU is doing

Why Timer Interrupts Are Essential:

Without timer interrupts, a process could run forever and never yield the CPU:

- If Process A has a bug (infinite loop), CPU would be stuck

- Other processes would never get to run

- System would appear frozen

With timer interrupts, the OS forces process switches:

Time 0-10ms: Process A running

Time 10ms: Timer fires (IRQ0)

CPU stops Process A mid-execution

Kernel saves A's state

Scheduler picks Process B

Dispatcher loads B's state

Time 10-20ms: Process B running

Time 20ms: Timer fires again

CPU stops Process B

Scheduler picks Process C

...

Quantum (Time Slice):

The interval between timer ticks is called the quantum or time slice (typically 1-100ms):

- Too small: excessive context switching overhead

- Too large: sluggish response time

- Sweet spot: 10-20ms on modern systems

Preemptive vs. Cooperative:

Preemptive (with timer):

- OS forces process to yield after quantum expires

- Ensures fairness

- One bad process cannot starve others

- Modern systems use preemptive scheduling

Cooperative (without timer):

- Process must voluntarily call

yield()orsleep() - If a process never yields, others starve

- Example: old Mac OS before OS X

What Happens in Timer ISR:

void timer_isr() {

// 1. Acknowledge timer hardware

acknowledge_timer();

// 2. Increment system tick counter

jiffies++;

// 3. Update current process's time used

current_process->time_used += QUANTUM;

// 4. If process exceeded quantum, mark for reschedule

if (current_process->time_used >= QUANTUM) {

current_process->state = READY;

reschedule_needed = true;

}

// 5. Call scheduler

if (reschedule_needed)

scheduler();

}Real-World Frequency:

Linux on x86 typically:

- Timer frequency: 100Hz (10ms quantum) or 1000Hz (1ms quantum)

- Can be adjusted via kernel parameter:

CONFIG_HZ - Higher frequency = more responsive but more overhead

Timer in Timesharing vs. Batch:

Timesharing: Timer fires frequently (high frequency) → quick context switches → responsive system

Batch: Timer might fire less frequently → longer quanta → fewer interrupts, but less responsive

Without the timer interrupt, timesharing systems would be impossible.

Problem 17

Define the essential properties of the following 2 types of operating systems: batch, timesharing.

Instructor Solution

A batch operating system is designed for high efficiency and throughput by grouping similar jobs into batches and executing them sequentially without manual intervention, making it ideal for large-scale, repetitive tasks like payroll processing. Its essential properties include the lack of direct user interaction during execution and a primary goal of maximizing CPU utilization. In contrast, a timesharing operating system focuses on minimizing response time to provide an interactive experience for multiple users simultaneously. It achieves this through round-robin CPU scheduling, where the processor rapidly switches between tasks using small “time slices” or quanta. This creates the illusion that each user has exclusive access to the system, supporting concurrent interactive sessions and real-time communication.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Batch and timesharing systems represent fundamentally different design philosophies:

Batch OS:

Goal: Maximize throughput (jobs completed per hour)

Use Cases:

- 1950s-1970s mainframes

- Modern scientific computing farms

- Off-peak system backups

- Nightly data processing jobs

Characteristics:

- No User Interaction: Jobs submitted as cards or tapes, run unattended

- Sequential Execution: One job completes before next starts

- Long Quantum: Processes run until I/O or completion

- Non-preemptive: OS doesn’t interrupt running jobs

- Batch Submission: Group similar jobs for efficiency

Example Schedule:

8:00 AM: Job 1 (payroll) starts

8:45 AM: Job 1 finishes → Job 2 (inventory) starts

9:30 AM: Job 2 finishes → Job 3 (reports) starts

10:15 AM: Job 3 finishes

Advantage: High CPU utilization; no wasted context switching Disadvantage: Terrible response time; no interactivity

Timesharing OS:

Goal: Minimize response time (user feels system is responsive)

Use Cases:

- Interactive desktop (Windows, Linux, macOS)

- Multi-user servers (shared systems)

- Real-time systems

- Mobile devices

Characteristics:

- Interactive: Users sit at terminals and expect quick feedback

- Concurrent Users: Multiple users logged in simultaneously

- Short Quantum: Context switches every 10-100ms

- Preemptive: OS forces process off CPU via timer interrupt

- Fair Scheduling: Each user/process gets regular CPU time

Example Schedule:

Time 0-10ms: User A's process runs

Time 10-20ms: User B's process runs

Time 20-30ms: User C's process runs

Time 30-40ms: User A's process runs again (round-robin)

Each user feels like they have exclusive access (though CPU actually multiplexes).

Comparison Table:

| Aspect | Batch | Timesharing |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Maximize throughput | Minimize response time |

| User Interaction | None (automated) | Interactive |

| Context Switches | Few (expensive) | Many (cheap cost) |

| Quantum | Long or variable | Short/fixed (10-100ms) |

| Response Time | Minutes/hours | Milliseconds |

| Users | One or non-existent | Multiple simultaneous |

| CPU Idle Time | Minimal | Some (user think time) |

| Example | Payroll processing | Linux desktop |

Key Insight:

Batch systems optimize for work done per unit time (throughput). Timesharing systems optimize for time to first response (latency).

A timesharing OS can run batch jobs, but with higher overhead due to frequent context switching.

Problem 18

Briefly define the following terms: (1) multi-tasking (2) timesharing. Does every timesharing OS have to be multi-tasking?

Instructor Solution

Multi-tasking is the ability of an OS to load multiple processes into memory and execute them concurrently by overlapping their CPU and I/O cycles to maximize efficiency. Timesharing is a logical extension of multi-tasking designed for interactive use, where the CPU distributes small “time slices” (quanta) to various users or tasks to ensure rapid response times, creating the illusion of exclusive hardware access. Consequently, every timesharing OS must be a multi-tasking OS because the mechanism of sharing time across multiple interactive sessions fundamentally relies on the ability to manage and switch between multiple tasks.

Elaboration (by LLM):

These terms are related but not identical:

Multi-tasking:

Definition: OS manages multiple processes in memory and switches CPU between them

Goal: Maximize CPU utilization by avoiding idle time

Mechanism:

- Keep multiple processes in memory

- When one blocks on I/O, run another

- Context switch between ready processes

Example:

Process A reads disk (blocked, waiting)

↓ (context switch)

Process B uses CPU while A waits

↓ (disk finishes, A becomes ready)

Process A continues (or B continues, depends on scheduler)

CPU-I/O Overlap:

Multi-tasking allows CPU and I/O to overlap, greatly improving utilization:

Without multi-tasking:

CPU: [A compute] [idle] [A compute] [idle]...

I/O: [disk] [disk]

With multi-tasking:

CPU: [A] [B] [C] [A] [B] [C]...

I/O: [A disk] [B disk]

CPU stays busy while I/O happens in parallel.

Timesharing:

Definition: OS divides CPU time into small slices and distributes fairly among users/processes

Goal: Provide interactive experience to multiple users simultaneously

Key Difference from Multi-tasking:

- Multi-tasking: Context switch when I/O or explicit yield

- Timesharing: Context switch periodically (timer-based) even if process is ready

Mechanism:

- Timer interrupt every 10ms

- Each process gets quantum of CPU time

- Preemptive scheduling (OS forces switch)

Example:

User A: [type] [wait] [type] [wait]...

^ ^

Process A runs A blocked on input

while waiting OS switches to B

Relationship:

Must Timesharing Systems Be Multi-tasking?

Yes, absolutely. Reasons:

- Multiple Concurrent Users: Timesharing requires multiple users/processes active simultaneously

- Context Switching: Timesharing depends on switching between multiple tasks

- Definition: Timesharing literally means “sharing time among multiple tasks”

You cannot have timesharing with a single process—that would just be a regular interactive OS.

Historical Examples:

| OS | Multi-task? | Timeshare? | Era |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNIX v6 | Yes | Yes | 1970s |

| DOS 1.0 | No | No | 1981 |

| Windows 3.x | Yes | No | 1985-1990 |

| Windows 95 | Yes | Yes | 1995 |

| Linux | Yes | Yes | 1991+ |

DOS was not multi-tasking; Windows 95 added preemptive multitasking/timesharing.

Why The Confusion?

In common usage, “multitasking” and “timesharing” are sometimes used interchangeably, but technically:

- Multitasking: capability to run multiple tasks

- Timesharing: specific scheduling strategy (timer-based, preemptive)

A more precise term is “preemptive multitasking,” which combines both concepts.

Problem 19

If your workload consists only of batch jobs, i.e., jobs that work in the background requiring no user interaction, would you use a timesharing OS? Why or why not? Briefly explain.

Instructor Solution

If your workload consists strictly of background batch jobs with no user interaction, you would not use a timesharing OS because its primary goal—minimizing response time—is unnecessary for non-interactive tasks. Timesharing systems introduce significant overhead due to frequent context switching and the management of “time slices,” which would actually decrease the overall throughput of your batch jobs. Instead, a simple multi-tasking OS would be more efficient, as these prioritize CPU utilization and throughput by allowing a job to run until it is finished or needs to wait for I/O, thereby completing the total workload in less time.

Elaboration (by LLM):

This decision hinges on understanding OS design goals and their cost-benefit tradeoffs:

Why NOT Timesharing for Batch?

The Core Issue:

Timesharing’s fundamental goal is minimizing response time, which has significant overhead costs:

| Overhead Component | Cost | Value for Batch | Value for Interactive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timer interrupts | ~0.1-1% CPU overhead | None | High (fairness) |

| Context switches | Cache flush, memory | Wastes resources | Necessary for fairness |

| Scheduling logic | CPU cycles per switch | Unnecessary | Necessary |

| Multi-level queues | Complexity overhead | Overkill | Needed for priority |

Concrete Example:

Batch Job (50s CPU + 1s I/O):

Timesharing OS:

- Timer fires every 10ms → 6000 context switches

- Each switch: save 30+ registers, flush cache

- Process again: 5000+ cycles of overhead

- Total overhead: ~5-10s lost to context switching

Batch OS:

- Job runs to completion or I/O block

- No timer interrupts

- 1-2 context switches per job (on I/O only)

- Total overhead: ~50-100ms

Why Multi-tasking (without Timesharing) is Better:

Multi-tasking still provides I/O overlap without timesharing overhead:

Job A: [compute 20s] [disk I/O 1s] [compute 30s] → total 51s

Job B: [compute 25s] [disk I/O 1s] [compute 25s] → total 51s

With simple multi-tasking (no time slices):

Timeline:

0-20s: Job A running

20-21s: Job A blocks on disk

21-46s: Job B running (A's I/O happens in parallel)

46-47s: Job B blocks on disk

47-50s: Job A finishes remaining 30s

50-51s: Job B finishes remaining 25s

Total: ~51s (I/O overlapped!)

With timesharing (timer every 10ms):

Add: context switches every 10ms even when no I/O

= more overhead, same 51s+ total time

Throughput vs. Latency:

| Metric | Batch (Goal) | Timesharing (Goal) |

|---|---|---|

| Jobs/hour | Maximize (throughput) | Less important |

| Response time | Irrelevant | Minimize (latency) |

| User happiness | Not waiting | Minimal wait time |

For batch: Users don’t care when job finishes, just that it finishes (ideally today). For interactive: User waiting at terminal wants immediate feedback (sub-second).

Why Multi-tasking Still Works:

Multi-tasking achieves CPU utilization without preemptive overhead:

- I/O Overlap: While Process A waits for disk, CPU runs Process B

- No Timer Overhead: Processes yield naturally when they block on I/O

- Simple Scheduling: FIFO queue, minimal scheduler overhead

- Cache Friendly: Long-running processes keep data cached

Real-World Comparison:

- Old IBM Mainframes: Batch-focused systems, no timesharing → high throughput for data processing

- Modern Linux: Timesharing → good for mixed interactive + batch workloads

- HPC Clusters: Often use simpler scheduling for batch jobs → better throughput

When Timesharing Makes Sense:

If you have a mixed workload (some interactive users + some batch jobs), timesharing handles both reasonably well, even with overhead.

But for pure batch? Overhead wastes CPU cycles that could be doing actual work.

Problem 20

Consider a system where I/O devices can only be programmed (controlled) with polling. Would a multitasking OS be able to increase CPU utilization in this system? Justify your answer.

Instructor Solution

In a system where I/O devices are controlled strictly via polling, a multi-tasking OS will not be able to increase CPU utilization. In an interrupt-driven system, the OS can increase utilization by switching to another task while one process waits for I/O; however, with polling, the CPU must actively and repeatedly check the device’s status in a “busy-wait” loop. Because the CPU itself is the mechanism performing the check, it remains occupied by the polling task and cannot be effectively reassigned to other work during the I/O wait period. Consequently, the CPU is “utilized” only in the sense that it is running instructions, but it is not performing productive work for other processes, essentially negating the primary efficiency benefit of multi-tasking.

Elaboration (by LLM):

This problem highlights the critical role of interrupts in making multi-tasking effective:

The Core Problem with Polling:

Polling is a “busy-wait” mechanism where the CPU continuously checks a device status register:

// Pseudo-code for polling

while (device.status != READY) {

// Spin in this loop, doing nothing productive

}

// Device is now ready

data = device.read();Key Issue: The CPU is tied up in the spinning loop; it cannot do other work.

Multi-tasking with Interrupts (Efficient):

Process A: [compute] [request disk read]

↓ (blocks, waiting for I/O)

CPU is freed up!

Process B runs: [compute useful work]

Meanwhile (async):

Disk device: [reading data...]

[data ready!]

[generates interrupt]

CPU response to interrupt:

- Save Process B state

- Handle interrupt, move data

- Wake up Process A

- Resume Process B or switch to A

CPU is utilized productively!

Multi-tasking with Polling (Inefficient):

Process A: [compute] [request disk read]

↓

Polls disk:

```

while (disk.busy) {

count++; // Waste CPU cycles

}

```

Process B: [can't run because A is polling!]

Disk device: [reading data...]

[data ready!]

[no interrupt capability]

Process A finally checks status: [data ready]

Process A: [resume compute]

Process B: Still blocked!

CPU is busy but doing nothing useful.

Why Multi-tasking Fails with Polling:

| Factor | Interrupts (Good) | Polling (Bad) |

|---|---|---|

| Device ready detection | Async (automatic) | Synchronous (loop) |

| CPU can do other work | Yes | No |

| Context switch trigger | Automatic | Must wait for poll |

| CPU utilization | High + productive | High + wasteful |

| Response time | Fast | Varies |

Real-World Analogy:

- Interrupt-driven: Waiter brings food when ready (async notification)

- Polling: Customer keeps asking “Is my food ready?” every second (busy-wait)

In both cases the system is “active,” but only the first is productive.

Why Polling Still Happens:

Some older or embedded systems use polling because:

- Simplicity: Easier to implement than interrupt handlers

- Legacy hardware: No interrupt support available

- Real-time constraints: Predictable polling timing (some edge cases)

But for general-purpose systems, interrupts are essential for multi-tasking.

Mathematical Comparison:

Assume: 1 disk I/O operation takes 100ms

With interrupts:

- Process A blocks (0 CPU used)

- Process B runs (100% CPU used)

- Total: 100ms of CPU work done

- Utilization: 100%

With polling:

- Process A spins in loop (100% CPU used, 0 work)

- Process B blocked (0 CPU used)

- Total: 0ms of useful CPU work done

- Utilization: 0% (busy but unproductive!)

Conclusion:

Multi-tasking only improves CPU utilization if the OS can take the CPU away from waiting processes. Polling-based systems don’t have this capability—the waiting process controls the CPU until I/O completes. Therefore, multi-tasking cannot increase utilization on polling-only systems.

Problem 21

Explain why it is necessary to re-implement your Linux program under Windows (for most non-trivial code).

Instructor Solution

It is necessary to re-implement a Linux program for Windows because the two operating systems provide entirely different System Call APIs. That is, the “abstractions” provided by the OS—such as how a program requests to open a file, create a process, or manage memory—differ significantly. Linux uses the POSIX standard and system calls like fork() and execv() whereas Windows relies on the Win32 API and calls like CreateProcess().

Elaboration (by LLM):

The root issue is that each OS defines its own interface between user-space programs and kernel services:

System Call API Differences:

| Task | Linux POSIX | Windows Win32 |

|---|---|---|

| Create process | fork() + execv() | CreateProcess() |

| Open file | open() | CreateFileA() |

| Read from file | read() | ReadFile() |

| Manage memory | mmap(), brk() | VirtualAlloc() |

| Create thread | pthread_create() | CreateThread() |

| Create pipe | pipe() | CreatePipe() |

| Signal handling | signal() | Windows events/waits |

Why These Differences Exist:

-

Design Philosophy Differences

- Linux: Follow UNIX tradition (everything is a file descriptor)

- Windows: Unique abstractions (HANDLEs, file paths)

-

Different Hardware Abstractions

- Linux targets UNIX-like behavior

- Windows abstracts Windows-specific concepts

-

Historical Evolution

- UNIX/POSIX: 50+ years of standardization

- Windows: Different lineage (DOS → Windows NT)

Example: Creating a Subprocess

Linux:

// Simple fork + exec pattern

pid_t child = fork(); // Clone current process

if (child == 0) {

execv("/bin/ls", args); // Replace process with /bin/ls

} else {

waitpid(child, NULL, 0); // Wait for child

}Windows:

// CreateProcess requires explicit setup

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

STARTUPINFO si = {0};

si.cb = sizeof(si);

CreateProcess(

"C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe", // Full path required

args,

NULL, NULL,

FALSE,

0,

NULL,

NULL,

&si,

&pi

);

WaitForSingleObject(pi.hProcess, INFINITE); // WaitWhy Not Just Translate?

Can a simple translation layer work?

// Attempt at wrapper

int fork() {

// Try to use CreateProcess to emulate fork

// Problem: fork() clones memory; CreateProcess doesn't

// Problem: fork() returns in parent AND child; CreateProcess returns only in parent

// This is fundamentally incompatible!

}Answer: Some APIs are incompatible at a conceptual level.

| Concept | Linux Behavior | Windows Behavior | Translation Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| fork() | Clone entire process | Launch separate exe | Hard (different model) |

| Signals | Async interrupts | Events/callbacks | Hard (different model) |

| File perms | Unix permissions | ACLs | Moderate (mapping) |

| Pipes | File descriptor-based | Named handles | Moderate (mapping) |

What About Portable Frameworks?

Libraries like Qt or wxWidgets provide abstraction layers:

// Qt (cross-platform)

QProcess p;

p.start("ls");

p.waitForFinished();

// Under the hood: calls fork+execv on Linux, CreateProcess on WindowsAdvantages: Write once, run anywhere (with library) Disadvantages:

- Library overhead

- Limited to what the library supports

- Still need to understand OS-specific concepts

High-Level Languages:

Languages like Python or Java provide abstraction:

# Python (works on both Linux and Windows)

import subprocess

subprocess.run(["ls"]) # Internally uses fork() on Linux, CreateProcess() on WindowsWhy Abstraction Matters:

High-level language (Python, Java):

↓

Standard library (subprocess module)

↓

├─→ Linux: fork() + execv()

└─→ Windows: CreateProcess()

↓

↓

OS kernel

The standard library handles the translation.

The Real Issue:

Low-level systems programming (C, C++, assembly) requires OS-specific calls because:

- Performance-critical code needs direct hardware access

- Abstractions add overhead

- Certain features are OS-specific (e.g., Linux

epoll, WindowsIOCP)

Conclusion:

Re-implementation is necessary because:

- System Call APIs differ fundamentally

- Design philosophies are different (UNIX vs. Windows)

- Some APIs have no direct equivalent (fork, signals)

- Performance-critical code avoids abstraction layers

However:

- High-level languages can abstract these differences

- Portable libraries (Qt, wxWidgets) help

- POSIX compliance tools (Cygwin, WSL) can bridge gaps

But for direct system calls and native APIs, re-implementation is necessary for non-trivial code.

Problem 22

Why is it necessary to have two modes of operation, e.g., user and kernel mode, in modern OSs? Briefly explain the difference between the user mode and kernel mode.

Instructor Solution

Modern OSs require dual-mode operation to provide system-wide protection, preventing user processes from accidentally or maliciously interfering with the core system or each other. In User Mode, software operates with restricted privileges, allowed to execute only a safe subset of CPU instructions and access its own private memory; this ensures that if a process crashes, the failure remains isolated. In contrast, Kernel Mode (privileged mode) grants the OS unrestricted access to all hardware, memory, and the full CPU instruction set. To perform protected operations—such as accessing a disk or network—a user program must execute a system call, which triggers a secure transition into kernel mode where the OS validates the request and executes it safely on the program’s behalf.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Dual-mode operation is the foundation of OS security and stability:

The Core Problem It Solves:

In early single-mode systems, any program could execute any instruction, leading to:

- One buggy program crashes entire system

- Malicious program could read other users’ data

- No resource isolation or protection

Example of Why This Matters:

// User program attempts dangerous operations

void *dangerous() {

// Direct I/O manipulation (no OS supervision)

outb(0x64, 0xFE); // Reboot the computer!

// Direct memory access (other processes' data)

int *someone_elses_memory = (int*)0x12345678;

*someone_elses_memory = 0; // Corrupt other process

// Disable interrupts (freeze the system)

cli(); // Clear interrupt flag

}In a single-mode system, this works (catastrophically). In dual-mode, these instructions are privileged and cause a General Protection Fault.

User Mode (Restricted Privileges):

| Capability | Allowed? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Execute code | Yes | Normal program execution |

| Read/write own mem | Yes | Program needs its own memory |

| Privileged instrs | No | Would break system integrity |

| Direct I/O | No | Could interfere with other tasks |

| Disable interrupts | No | Would freeze the system |

| Modify page tables | No | Would break memory isolation |

| Access other memory | No | Violates privacy and protection |

User Mode Example:

// Safe operations allowed

int x = 5; // ✅ Access own memory

int y = x + 10; // ✅ CPU arithmetic

printf("Hello\n"); // ✅ Library call (eventually syscall)

FILE *f = fopen(...); // ✅ This triggers syscall (transitions to kernel)Kernel Mode (Full Privileges):

| Capability | Allowed? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Any user operation | Yes | Must handle user tasks |

| Privileged instrs | Yes | Control hardware |

| Direct I/O | Yes | Manage devices |

| Access all memory | Yes | Manage all resources |

| Interrupt control | Yes | Schedule processes |

| Page table mods | Yes | Manage virtual memory |

Mode Bit in CPU:

The CPU has a single bit in the status register to track current mode:

Mode Bit = 0: Kernel Mode (privileged)

Mode Bit = 1: User Mode (restricted)

When instruction executes:

if (instruction is privileged && mode_bit == 1) {

trigger_general_protection_fault();

}

Transitions Between Modes:

User → Kernel (via system call):

User program:

mov $40, %eax # System call number (40 = add)

int $0x80 # Trap instruction

Hardware actions (automatic):

1. Save user state (registers, PC)

2. Set mode_bit = 0 (enter kernel)

3. Jump to kernel handler at interrupt vector 0x80

Kernel code runs (now in kernel mode):

- Validate parameters

- Execute privileged operations

- Perform actual work

Kernel → User (via iret):**

iret # Return from interrupt

Hardware actions:

1. Restore user state (registers, PC)

2. Set mode_bit = 1 (return to user)

3. Resume user code exactly where it stopped

Why Both Modes Are Necessary:

| Requirement | User Only | Kernel Only | Both (Dual) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Run user programs | ✅ | ✅ (slow) | ✅ |

| Protect against buggy programs | ❌ | ✅ (can’t) | ✅ |

| Efficient OS operations | ❌ | ✅ (only) | ✅ |

| Manage hardware directly | ❌ | ✅ (only) | ✅ |

Real-World Protection Examples:

Example 1: Faulty Program

void buggy_function() {

int *p = NULL;

*p = 42; // Segmentation fault

}With Dual-Mode:

- Program runs in user mode

- Illegal memory access detected by CPU

- Hardware triggers General Protection Fault (interrupt)

- OS catches fault, terminates offending process only

- Other processes continue running unaffected

- System stays up

Without Dual-Mode (hypothetical):

- Program could corrupt kernel memory

- Entire system crashes

- All running programs lost

Example 2: Malicious Program

void malicious() {

// Try to read another user's password file

FILE *f = fopen("/home/otheruser/.ssh/id_rsa", "r");

}With Dual-Mode + File Permissions:

- User mode program cannot bypass OS security checks

open()syscall checks permissions in kernel mode- OS validates that user has access rights

- If not, syscall returns error

Without Dual-Mode:

- Program could bypass all checks

- Direct memory access to retrieve password

- Security completely compromised

Performance Consideration:

Cost of Dual-Mode:

Every system call incurs context switching overhead:

- Save user state (~100s of CPU cycles)

- Validate parameters (~10s of cycles)

- Execute privileged instruction

- Restore user state (~100s of cycles)

Why It’s Worth It:

The overhead is small compared to:

- Value of system stability

- Cost of attacks/data loss

- Cost of recovering from system crashes

Modern Extensions:

Modern CPUs have more than 2 modes:

- Intel: Rings 0-3 (kernel at ring 0, user at ring 3)

- ARM: Multiple privilege levels (EL0-EL3)

- Virtualization extensions: Additional modes for hypervisors

Conclusion:

Dual-mode operation is essential because:

- Process Isolation: One process can’t crash others

- Resource Protection: Prevents unauthorized access

- System Integrity: OS maintains control of hardware

- Security: Enforces access control policies

- Stability: Bugs are contained, don’t affect entire system

Without it, any program could compromise the entire system.

Problem 23

How does the OS change from the user mode to the kernel mode and vice versa?

Instructor Solution

The transition from user to kernel mode is triggered by a hardware interrupt, a software trap (exception), or the execution of a specific system call instruction (e.g., int, sysenter, or syscall). The CPU tracks the current privilege level using a mode bit in the status register—typically 1 for user mode and 0 for kernel mode—which is automatically flipped during these events to grant the OS full access to system resources. Once the kernel completes the requested task, the transition from kernel back to user mode is performed via a privileged “return from interrupt - iret” or “system return – sysexit or sysret” instruction. This instruction atomically resets the mode bit to 1, restores the saved process state (including the program counter), and resumes the user program exactly where it left off.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Mode transitions are one of the most critical OS mechanisms:

User → Kernel Transition (Three Types):

The OS can enter kernel mode via:

-

System Call (Intentional Software Trap)

User code: mov $40, %eax # System call number int $0x80 # Trap instruction (x86) Hardware actions: 1. Recognize int $0x80 instruction 2. Look up interrupt vector 0x80 in Interrupt Vector Table (IVT) 3. Push user registers onto kernel stack 4. Set privilege mode bit to 0 (kernel) 5. Jump to handler at address from IVT[0x80] -

Hardware Interrupt (External/Async)

Device hardware: [Timer expires after 10ms] [Disk finishes I/O operation] [Keyboard key pressed] Hardware actions: 1. Device sends electrical signal to CPU 2. CPU finishes current instruction 3. Push registers onto kernel stack 4. Set privilege mode bit to 0 5. Jump to appropriate interrupt handler -

Exception/Fault (Internal CPU Event)

User code executing: mov $10, %eax int $0 # Divide by zero? Page fault? Illegal instruction? CPU detects: 1. Invalid operation 2. Triggers internal exception 3. Same as interrupt: save state, flip mode bit, jump to handler

Mode Bit Implementation (x86-64):

The RFLAGS register contains privilege information:

Bit 0: CF (Carry Flag)

...

Bit 2: PF (Parity Flag)

...

Bits 12-13: IOPL (I/O Privilege Level) - only modifiable in kernel

...

Bit 17: VM (Virtual-8086 Mode)

Not a single "mode bit" but privilege level bits!

Actually, mode is determined by:

- Current Privilege Level (CPL) in CS register

- If CPL == 0: Kernel mode

- If CPL == 3: User mode

The Interrupt Vector Table (IVT):

When int 0x80 executes, CPU uses 0x80 to index into IVT:

// IVT structure (x86)

typedef struct {

uint16_t offset_low; // Low 16 bits of handler address

uint16_t selector; // Code segment

uint16_t attributes; // Type, privilege, present bit

uint16_t offset_high; // High 16 bits (32-bit) or 32 bits (64-bit)

} idt_entry_t;

idt_entry_t idt[256]; // 256 possible interrupt vectors

// When int 0x80 executes:

handler_address = idt[0x80].offset;

kernel_code_segment = idt[0x80].selector;

// CPU jumps to handler_address in kernel_code_segmentKernel → User Transition (Return):

After kernel handles the request:

Kernel code:

// Finished handling system call

// Restore user registers from kernel stack

// etc.

iret # Return from interrupt instruction

Hardware actions:

1. Pop user registers from kernel stack (including program counter)

2. Set privilege mode bit back to 1 (user mode)

3. Jump to resumed user address (from popped program counter)

4. User code continues exactly where it left off

The Atomic Nature of Mode Switch:

Mode changes must be atomic (indivisible):

// ILLEGAL (if user could do this):

mode_bit = 0; // Enter kernel

// ... malicious kernel code here

mode_bit = 1; // Back to user

// If allowed, user programs could:

// 1. Flip mode bit to 0

// 2. Execute privileged instructions

// 3. Flip mode bit back to 1

// 4. System is compromised!

Solution: Hardware-enforced atomicity

- Only CPU can flip mode bit

- Only during recognized events (system call, interrupt, exception)

- User code cannot execute these instructions directly

Example: Full System Call Execution

// User program

int fd = open("/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY);

// Assembly (what actually happens):

.user_code:

mov $2, %eax # Syscall number (2 = open on Linux x86)

mov $path, %ebx # arg1: filename

mov $O_RDONLY, %ecx # arg2: flags

int $0x80 # TRAP to kernel (mode changes here!)

.kernel_handler (automatic, can't be avoided):

// Now executing in kernel mode

// Privilege level has changed

// Can execute privileged instructions

// Validate syscall number in eax

cmp $NR_SYSCALLS, %eax

jge invalid_syscall

// Call system call handler

call *sys_call_table(,%eax,8) // Call appropriate handler

// Handler returns, result in eax

iret # RETURN to user (mode changes back here!)

.user_code (resumed):

// Back in user mode

// fd now contains file descriptor or error codeStack Switch:

During mode transition, CPU also switches stack pointers:

User-space stack (User Mode):

[user variables]

[local variables]

[return addresses]

Kernel-space stack (Kernel Mode):

[saved user registers]

[kernel local variables]

[kernel work data]

On syscall:

1. Push user state to kernel stack

2. Switch stack pointer from user_sp to kernel_sp

On return:

1. Pop saved user state from kernel stack

2. Switch stack pointer back to user_sp

3. Resume user execution

Why This Matters:

| Requirement | Mechanism | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Security boundary | Mode bit + privileged instr | User can’t escape kernel |

| State consistency | Atomic transition | No partial-mode states |

| OS control | Only kernel can flip mode | OS maintains authority |

| Protection against bugs | Exceptions handled by OS | Crashes contained |