Process Management Practice Problems

Problem 1: Programs vs Processes

What’s the difference between a program and a process?

Instructor Solution

A program is a passive entity—a static file stored on a disk (like an .exe or an ELF binary) that contains a set of compiled instructions and data. In contrast, a process is an active, dynamic entity; it is an instance of a program in execution. When you launch a program, the OS creates a process by loading the code into RAM, allocating a unique Process ID (PID), and assigning it system resources such as a stack, a heap, and a set of CPU registers.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Program vs Process: A Fundamental Distinction

The Core Difference:

A program is static (unchanging), while a process is dynamic (changing state during execution).

Program:

- File on disk (stored in persistent storage)

- Contains machine instructions and data

- Read-only until executed

- One program can create many processes

- Example: The

/bin/lsfile is a program

Process:

- Active instance of a program in RAM

- Has current state: registers, memory, open files, I/O buffers

- Changes during execution (variables change, heap grows, stack shrinks)

- Each process is independent

- Example: When you type

lsin terminal, a new process is created

Concrete Example:

On disk:

/usr/bin/firefox ← One program file

In RAM (after you click Firefox icon):

Process 1: firefox (PID 1234) ← First instance

Process 2: firefox (PID 1235) ← Second instance (opened new window)

Process 3: firefox (PID 1236) ← Third instance

Each process:

- Has its own memory space

- Has its own set of open files

- Has its own registers/CPU state

- But all three execute the same binary code

What the OS Creates:

When you launch a program, the OS:

- Loads the binary from disk into RAM

- Allocates a stack (for local variables, function calls)

- Allocates a heap (for dynamic memory)

- Assigns a Process ID (PID)

- Creates a Process Control Block (PCB) to track state

- Sets up page tables for virtual memory isolation

- Opens standard file descriptors (stdin, stdout, stderr)

Why This Matters:

- You can run the same program multiple times simultaneously (each as a separate process)

- Each process is isolated from others (one crash doesn’t crash the others)

- The OS can schedule processes independently on available CPU cores

- Memory/resources are tracked per-process

Resource Difference:

Program: 1 copy on disk (5MB executable file)

Three running instances:

Process 1: ~50MB in RAM (code + heap + stack)

Process 2: ~50MB in RAM

Process 3: ~50MB in RAM

Total: 150MB RAM, but same 5MB disk file

The disk file is shared; the RAM allocations are not.

Problem 2: Address Space Sections

List the 4 sections of the address space of a process. Briefly describe what’s stored in each section.

Instructor Solution

Code: Contains the executable binary instructions.

Data: Stores global and static variables.

Heap: Stores dynamically allocated variables (e.g., via malloc or new).

Stack: Stores temporary data such as local variables, function parameters, and return addresses.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Process Address Space Layout

Memory Layout (x86-32 Linux):

High Address (0xFFFFFFFF)

┌─────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │ 0xC0000000+

│ (OS kernel runs) │

└─────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────┐

│ Stack (grows ↓) │ Local vars, parameters

├─────────────────────┤

│ │

│ (unallocated) │

│ │

├─────────────────────┤

│ Heap (grows ↑) │ malloc(), new

├─────────────────────┤

│ Data Segment │ Globals, statics

├─────────────────────┤

│ Code Segment │ Instructions

└─────────────────────┘

Low Address (0x00000000)

The Four Sections:

1. Code Segment (Text Segment):

- Contains machine instructions (the executable program)

- Read-only (prevents accidental modification of code)

- Shared among all running instances of the program

- Fixed size at compile time

- Example:

int main() {

printf("Hello"); ← These instructions are in Code segment

return 0; ← This instruction is in Code segment

}2. Data Segment:

- Global and static variables that are initialized

- Read-write (can be modified during execution)

- Exists for the entire process lifetime

- Fixed size at compile time

- Example:

int global_var = 42; ← In Data segment (initialized to 42)

static int static_var = 100; ← In Data segment (initialized to 100)

int main() {

global_var = 50; ← Can modify, still in Data segment

}BSS Segment (Uninitialized Data):

- Sometimes considered separate from Data

- Global and static variables that are uninitialized or initialized to zero

- Occupies no disk space (just a count of bytes)

- Zeroed out when process starts

- Example:

int uninitialized_global; ← In BSS segment (zero'd at startup)

static int zero_var = 0; ← In BSS segment3. Heap:

- Dynamically allocated memory (at runtime, not compile time)

- Grows upward (toward higher addresses) as allocation happens

- Shrinks when memory is freed

- Shared by all dynamic allocations in a process

- Fragmentation can occur

- Example:

int *arr = malloc(1000 * sizeof(int)); ← Memory comes from Heap

← Size not known at compile time

free(arr); ← Returns memory to HeapHeap Characteristics:

- Programmer-controlled allocation (malloc/free or new/delete)

- Must be manually freed (memory leak if not freed)

- Slower than stack (requires heap manager)

- Larger space available (typically megabytes to gigabytes)

4. Stack:

- Temporary storage for function-local variables

- Function parameters and return addresses

- Grows downward (toward lower addresses) as function calls nest

- Shrinks when functions return

- Very fast allocation (just move stack pointer)

- Automatic deallocation (when function returns)

- Limited size (typically megabytes)

- Example:

void foo() {

int x = 5; ← Local var in Stack

int y = 10; ← Local var in Stack

bar(); ← Return address pushed to Stack

}

void bar() {

int z = 20; ← Local var in Stack (on top of x, y)

} ← z automatically freed when bar() returnsStack vs Heap:

| Characteristic | Stack | Heap |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Very fast (1-2 cycles) | Slower (requires search) |

| Size | Limited (~8MB default) | Large (gigabytes) |

| Allocation | Automatic (LIFO) | Manual (malloc/free) |

| Lifetime | Until function returns | Until freed |

| Overflow | Stack overflow crash | Fragmentation |

| Sharing | Per-thread (isolated) | Process-wide (shared) |

Memory Layout Example:

int global = 5; // Data Segment

static int s = 10; // Data Segment

char* ptr; // Data Segment (pointer itself)

int main() {

int local = 20; // Stack

static int s2 = 30; // Data Segment

int* heap_ptr = malloc(100); // Stack: heap_ptr pointer

// Heap: 100 bytes of data

return 0;

}Real-World Impact:

- Speed: Local variables (stack) are fastest

- Memory: Large data structures should use heap

- Safety: Stack is safer (automatic cleanup)

- Debugging: Stack overflow is obvious; heap corruption is subtle

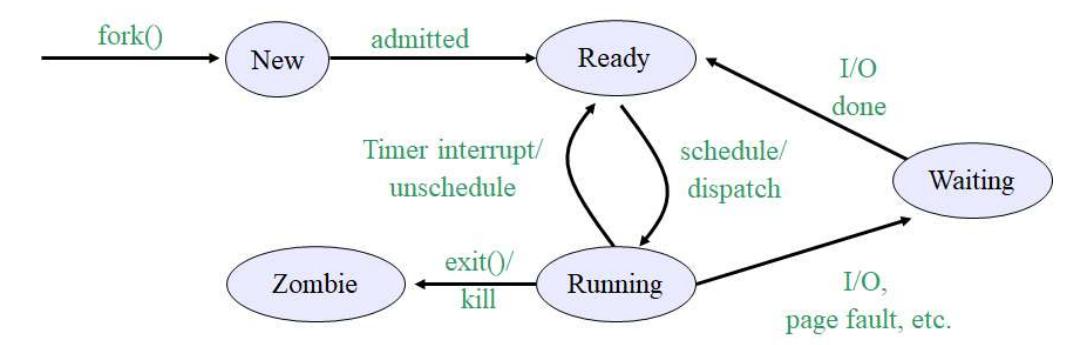

Problem 3: Process Transition Diagram

Draw the process transition diagram. Mark each transition appropriately.

Instructor Solution

Elaboration (by LLM):

The Five Process States: A Complete Lifecycle

A process doesn’t simply run continuously. Instead, it moves through distinct states based on resource availability and system decisions. This diagram shows the five fundamental process states in most operating systems.

The Five States Explained

1. New State

Purpose: Process just created, not yet admitted by OS

Entry: fork() or exec() system call

Exit: When OS admits it to Ready queue

Characteristics:

- PCB created

- Memory not yet allocated

- Not yet competing for CPU

- Process initialization code not yet run

2. Ready State

Purpose: Process is prepared to run, waiting for CPU time

Entry: Admitted from New, or time slice expired, or I/O completes

Exit: Scheduler selects for CPU (dispatch)

Characteristics:

- All resources allocated except CPU

- In memory, context saved

- Waiting for scheduler decision

- Can run immediately if scheduled

3. Running State

Purpose: Process actively executing on CPU

Entry: Scheduled from Ready queue (dispatch/schedule)

Exit: Time slice expires, I/O needed, or process terminates

Characteristics:

- Occupying CPU time slice

- Actually executing instructions

- Can be preempted at any time

- Only ONE process per CPU (single-core system)

4. Waiting State (Blocked)

Purpose: Process waiting for event (I/O, lock, etc.)

Entry: I/O request, page fault, or waiting for resource

Exit: Event occurs (I/O done, page returned to memory)

Characteristics:

- Process cannot run even if CPU available

- Waiting for external event

- Does not consume CPU

- Returns to Ready when event completes

5. Zombie State

Purpose: Process terminated but not yet cleaned up

Entry: exit() or kill signal received

Exit: Parent calls waitpid() (process reaped)

Characteristics:

- Code/memory freed

- PCB still exists in kernel

- Holding exit status for parent

- Cannot be killed (already dead)

Transitions: When and Why States Change

New → Ready: “admitted”

Trigger: OS schedules process admission

Decision: OS checks resource availability (memory, PIDs available)

Time: Microseconds after fork()

Example:

fork() called

OS checks: "Is there memory?"

OS checks: "Are we at PID limit?"

If YES → process admitted to Ready

If NO → process stays in New (waits)

Ready → Running: “schedule/dispatch”

Trigger: Scheduler selects process from Ready queue

Algorithm: Round-robin, priority-based, fair scheduling, etc.

Frequency: Every time slice (10-100ms typical)

Who decides: Scheduler/dispatcher (kernel component)

Example:

Process in Ready queue for 5ms

Timer interrupt occurs

Scheduler picks this process

Context switch → Now Running

Running → Ready: “Timer interrupt/unschedule”

Trigger: Time slice expires

Hardware: Timer interrupt fires

Action: Scheduler preempts process, saves context

Effect: Process returns to Ready (not Waiting!)

Reason: Process wasn't blocked, just had its turn

Example:

Process A running for 10ms (its time slice)

Timer fires: "Time's up!"

Context saved

Process A → Back to Ready queue

Scheduler picks Process B

Running → Waiting: “I/O, page fault, etc.”

Trigger: Process needs resource not immediately available

Examples:

- Reading disk file (I/O request)

- Page fault (memory access to disk-backed page)

- Waiting for lock (mutex, semaphore)

- Waiting for network data

Action: Process voluntarily gives up CPU

Effect: Process blocked, won't run until event completes

Example:

Process reads(disk_file)

OS: "This will take milliseconds"

Process moved to Waiting

Scheduler picks another process

Waiting → Ready: “I/O done, page fault resolved, etc.”

Trigger: Event completion (I/O, page return, lock released)

Who initiates: Device interrupt handler or another process

Effect: Process moves back to Ready (next in line for CPU)

Time: Could be immediate or delayed

Example:

Process waiting for disk read

Disk finishes, sends interrupt

Kernel: "Data ready!"

Process → Waiting

Next scheduler cycle: Process moved to Ready

Running → Zombie: “exit()/kill”

Trigger: Process calls exit() or receives SIGKILL/SIGTERM

Action: Kernel terminates process

Effect: Memory freed, PCB remains, exit status stored

Parent notification: Process becomes zombie awaiting waitpid()

Example:

Process calls exit(0)

Kernel frees code, data, stack memory

PCB (Process Control Block) stays in memory

Zombie state until parent calls waitpid()

Zombie → (removed): “waitpid()”

Trigger: Parent calls waitpid(child_pid, &status, 0)

Action: Kernel retrieves exit status, frees PCB

Effect: Process completely removed from system

Time: Can happen immediately after child exit, or days later

Example:

Parent: waitpid(pid)

Kernel: Gets zombie's exit code

Kernel: Frees PCB and PID slot

Process fully gone

State Diagram as a State Machine

Entry point: Fork called

│

▼

┌──────────┐

│ New │ ← Process created but not yet run

└──────────┘

│

Admitted to system

│

▼

┌──────────┐

┌──────▶│ Ready │ ◀──────┐

│ │ (Queue) │ │

│ └──────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ Scheduled │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ Running │ │

│ │(CPU time)│ │

│ └──────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ Timer interrupt

│ │ │ (time slice done)

│ I/O │ └────────┘

│ needed│

│ ▼

│ ┌──────────┐

└───│ Waiting │ (blocked on I/O)

│(Blocked) │

└──────────┘

│

I/O done

│

└────────────────┐

│

Ready queue

│

▼

Running → exit() or kill signal

│

▼

┌──────────┐

│ Zombie │ (terminated, awaiting reaping)

│(Defunct) │

└──────────┘

│

waitpid()

│

▼

(Process removed completely)

Real-World Example: Browser Process Lifecycle

Time 0: User double-clicks Firefox icon

fork() + exec() → New state

OS admits → Ready state

Time 5ms: Scheduler selects Firefox

Firefox → Running

Starts loading libraries from disk

Time 15ms: Disk I/O needed to load library

Firefox → Waiting (blocked on disk read)

Scheduler selects another process

Time 18ms: Disk returns data (interrupt)

Firefox → Ready (back in queue)

Time 20ms: Scheduler selects Firefox again

Firefox → Running

Draws window on screen

Time 25ms: User clicks "Open File" dialog

Disk I/O needed

Firefox → Waiting

Time 30ms: I/O done

Firefox → Ready

Time 1hr: User closes Firefox

Firefox calls exit()

Firefox → Zombie (waiting for parent shell)

Time 1hr+1s: Shell's waitpid() catches exit status

Firefox PCB freed → completely gone

Why Multiple States Are Necessary

Without Ready state (just New/Running/Waiting):

Problem: How do we queue waiting processes?

Problem: Multiple processes can't wait simultaneously

Problem: Scheduler can't pick who runs next

Result: System can only handle one process at a time

Without Waiting state (just Ready/Running):

Problem: Where do I/O blocked processes go?

Problem: CPU wastes cycles waiting for I/O

Problem: System can't be responsive

Result: Throughput plummets, responsiveness terrible

Without Zombie state (immediate PCB deletion):

Problem: Parent can't get child's exit status

Problem: Child's fate unknown to parent

Problem: Parent doesn't know if child crashed or succeeded

Result: No error handling, parent can't know what happened

All five states are essential for modern process management.

Key Insight: Only One State Per Process

A process is always in exactly one state:

// Impossible situations:

Process in both Ready AND Waiting? ❌ NO

Process in Running AND Ready? ❌ NO

Process in New AND Running? ❌ NO

// Correct: Always exactly one

Process is in Ready queue ✅ YES

Process is blocked on disk I/O ✅ YES

Process is running on CPU ✅ YES

Process is terminated (Zombie) ✅ YES

Process is being created (New) ✅ YESThe state machine ensures clarity about each process’s exact situation at all times.

Problem 4: Process ID Assignment

Why is it necessary for the OS to assign a unique process id to each process in the system?

Instructor Solution

The OS assigns a unique Process ID (PID) to provide a clear, unambiguous handle for managing the lifecycle and security of every active entity in the system. Because multiple instances of the same program (like three separate browser windows) share the same executable name, the PID allows the kernel to distinguish between them when allocating CPU time, protecting memory boundaries, and tracking resource ownership. Without unique IDs, the OS would be unable to signal, monitor, or terminate a specific process without risk of affecting others, effectively breaking the fundamental isolation required for multitasking.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Why Process IDs Are Essential

The Problem Without PIDs:

Imagine running three Firefox windows simultaneously. Without PIDs, how would the OS know which one to preempt? How would you kill one specific Firefox without killing all of them?

Without PIDs:

User: "Pause Firefox"

OS: Which one?? All three of them? Just one?

With PIDs:

User: "Kill process 1234"

OS: Done. The other Firefox windows (PIDs 1235, 1236) keep running

Main Uses of PID:

1. Identification and Uniqueness:

- Each PID is globally unique within the system at any given time

- PIDs can be reused only after a process terminates

- Allows unambiguous reference to a specific process

2. Tracking Resource Ownership:

Process 1234 (PID=1234):

- Owns 5 open files

- Allocated 50MB RAM

- Using CPU time

- Has 3 child processes

OS must track: which resources belong to which PID

3. Process Signaling:

// Parent process

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Send signal to specific PID 1234

// (not to any other process)4. Hierarchy and Parent-Child Relationships:

PID 1 (init)

├─ PID 100 (shell)

│ ├─ PID 1234 (Firefox)

│ ├─ PID 1235 (Firefox)

│ └─ PID 1236 (Firefox)

└─ PID 200 (other process)

When PID 100 (shell) terminates:

OS must find all children (1234, 1235, 1236)

and reassign them to init (PID 1)

5. Privilege and Security:

// Only allowed to signal your own processes

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Your process → OK

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Root's process → DeniedPID in Linux:

$ ps aux | grep firefox

user 1234 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1234

user 1235 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1235

user 1236 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1236

$ kill 1234 # Kills only PID 1234 (one Firefox window)

# PID 1235 and 1236 unaffectedPID Allocation:

- Linux starts at PID 1 (init/systemd)

- Increments with each new process: 2, 3, 4, …

- Reaches

pid_max(usually 32768 or 4194304 in modern systems) - Wraps around when exhausted

- Avoids reusing PIDs that are still active

Without PIDs, Multitasking Would Be Impossible:

| Operation | Without PIDs | With PIDs |

|---|---|---|

| Run program | OS doesn’t know which | OS assigns PID, tracks state |

| Pause process | Can’t target a specific one | kill -STOP <PID> |

| Monitor usage | Can’t track resources | ps -p <PID> |

| Terminate | Risk killing all instances | kill <PID> kills only one |

| Parent-child | No family tree | getppid() returns parent |

Real-World Impact:

Without PIDs, you couldn’t:

- Run multiple Firefox windows

- Kill one hung process without killing others

- Monitor CPU usage per program

- Enforce privilege restrictions per process

- Implement job control in the shell

Elaboration (by LLM):

Why Process IDs Are Essential

The Problem Without PIDs:

Imagine running three Firefox windows simultaneously. Without PIDs, how would the OS know which one to preempt? How would you kill one specific Firefox without killing all of them?

Without PIDs:

User: "Pause Firefox"

OS: Which one?? All three of them? Just one?

With PIDs:

User: "Kill process 1234"

OS: Done. The other Firefox windows (PIDs 1235, 1236) keep running

Main Uses of PID:

1. Identification and Uniqueness:

- Each PID is globally unique within the system at any given time

- PIDs can be reused only after a process terminates

- Allows unambiguous reference to a specific process

2. Tracking Resource Ownership:

Process 1234 (PID=1234):

- Owns 5 open files

- Allocated 50MB RAM

- Using CPU time

- Has 3 child processes

OS must track: which resources belong to which PID

3. Process Signaling:

// Parent process

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Send signal to specific PID 1234

// (not to any other process)4. Hierarchy and Parent-Child Relationships:

PID 1 (init)

├─ PID 100 (shell)

│ ├─ PID 1234 (Firefox)

│ ├─ PID 1235 (Firefox)

│ └─ PID 1236 (Firefox)

└─ PID 200 (other process)

When PID 100 (shell) terminates:

OS must find all children (1234, 1235, 1236)

and reassign them to init (PID 1)

5. Privilege and Security:

// Only allowed to signal your own processes

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Your process → OK

kill(1234, SIGTERM); // Root's process → DeniedPID in Linux:

$ ps aux | grep firefox

user 1234 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1234

user 1235 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1235

user 1236 ... /usr/bin/firefox ← PID 1236

$ kill 1234 # Kills only PID 1234 (one Firefox window)

# PID 1235 and 1236 unaffectedPID Allocation:

- Linux starts at PID 1 (init/systemd)

- Increments with each new process: 2, 3, 4, …

- Reaches

pid_max(usually 32768 or 4194304 in modern systems) - Wraps around when exhausted

- Avoids reusing PIDs that are still active

Without PIDs, Multitasking Would Be Impossible:

| Operation | Without PIDs | With PIDs |

|---|---|---|

| Run program | OS doesn’t know which | OS assigns PID, tracks state |

| Pause process | Can’t target a specific one | kill -STOP <PID> |

| Monitor usage | Can’t track resources | ps -p <PID> |

| Terminate | Risk killing all instances | kill <PID> kills only one |

| Parent-child | No family tree | getppid() returns parent |

Problem 5: Process Control Block

What is a Process Control Block (PCB)? What is it used for? List 1 item that must be stored in a PCB.

Instructor Solution

A Process Control Block (PCB) is a vital data structure in the operating system’s kernel that serves as the “identity card” or repository for all information associated with a specific process. It is used by the OS to manage process execution, allowing the kernel to perform context switching by saving the state of a running process so it can be resumed later exactly where it left off. One essential item stored in a PCB is the process id (pid) that uniquely identifies the process in the OS kernel.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The Process Control Block: The OS's Memory of Each Process

The PCB is essentially the process’s resume file. When the OS pauses a process, it must save everything needed to resume execution later. When another process needs to run, the OS switches to its PCB to restore its state.

What is a PCB?

A Process Control Block is a data structure (typically a C struct in kernel code) that the OS maintains for every process. It contains all the information the OS needs to manage that process.

// Simplified Linux PCB (actually much larger)

struct task_struct {

pid_t pid; // Process ID

char comm[16]; // Command name

int state; // TASK_RUNNING, TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE, etc.

unsigned long *stack; // Kernel stack pointer

struct mm_struct *mm; // Memory management info

// ... hundreds more fields

};Why Is the PCB Necessary?

Scenario: The Context Switch

Time T=0: Process A (PID 1234) running

CPU registers: PC=0x8048500, R1=42, SP=0xBFFF0000

Time T=1: Timer interrupt! OS says "Your time is up, Process A"

OS saves Process A's state to PCB_A:

PCB_A.PC = 0x8048500

PCB_A.R1 = 42

PCB_A.SP = 0xBFFF0000

Time T=2: OS loads Process B's state from PCB_B:

CPU registers: PC=0x8048800, R1=99, SP=0xCFFF0000

Time T=3: Process B runs exactly where it left off

Time T=4: Another interrupt, Process A loads from PCB_A

Resumes at PC=0x8048500 with R1=42, SP=0xBFFF0000

(exactly as if it was never interrupted!)

Without a PCB:

- OS would have nowhere to save Process A’s state

- When switched back, Process A wouldn’t know where it was

- Execution would be corrupted

Core PCB Components

1. Process Identification:

int PID; // This process's unique ID

int PPID; // Parent's PID (for cleanup when parent dies)

int UID; // Owner's user ID (for security)2. CPU Register State (Context):

// ALL CPU registers must be saved

uint32_t PC; // Program Counter (what instruction to run next)

uint32_t SP; // Stack Pointer

uint32_t BP; // Base Pointer

uint32_t R0, R1, R2, ... R15; // General-purpose registers

uint32_t flags; // CPU flags (zero flag, carry flag, etc.)This is the most critical part for context switching.

3. Process State:

enum State {

CREATED, // Just created

READY, // Waiting for CPU

RUNNING, // Currently on CPU

BLOCKED, // Waiting for I/O

SUSPENDED, // Paused by debugger

TERMINATED // Done, waiting for cleanup

};The OS uses this to decide which queue the process belongs to.

4. Memory Management:

struct MMStruct {

PageTable* page_table; // Virtual→physical address mapping

uint32_t text_start; // Code segment base

uint32_t data_start; // Data segment base

uint32_t heap_start; // Heap base

uint32_t stack_limit; // Lowest valid stack address

};Without this, the OS couldn’t translate the process’s virtual addresses to physical memory.

5. I/O and File Management:

File* open_files[256]; // Pointers to open file structures

// Index 0 = stdin, 1 = stdout, 2 = stderrWhen the process does read(3, buffer, 100), the OS uses PCB->open_files[3] to find the file.

6. Scheduling Information:

int priority; // Higher = more important

uint32_t time_quantum; // How long until preemption

uint32_t cpu_time_used; // Total CPU time accumulatedThe scheduler uses priority to decide which ready process gets CPU next.

PCB in Action: Real Example

$ ps aux | grep bash

user 1234 0.0 0.1 2345 2000 pts/0 S 14:32 0:00 /bin/bash

user = UID (owner of process)

1234 = PID

2345 = Virtual memory size (from PCB)

2000 = Resident set size (from PCB)

S = State (Sleeping/Ready) (from PCB)

0:00 = CPU time used (from PCB)All this information comes directly from the PCB!

Why Each Field Is Essential

| PCB Field | Purpose |

|---|---|

| PID | Uniquely identify process |

| Registers | Save/restore CPU state during context switch |

| Memory info | Translate virtual addresses to physical RAM |

| State | Know which queue process belongs in |

| Priority | Decide scheduling order |

| Files | Know what files/devices process has open |

| CPU time | Track resource usage for billing/fairness |

Without a PCB, the OS couldn’t:

- Context switch (no place to save state)

- Run multiple processes (no way to resume)

- Enforce memory protection (no isolation info)

- Schedule fairly (no priority tracking)

- Track resource usage (no accounting)

- Clean up when process terminates (no file list)

Think of it this way: A PCB is like a passport for a process. When the process needs to leave the CPU, its “passport” (PCB) stays with the kernel. When it’s time to return to the CPU, the OS uses the passport to restore everything that was saved.

Problem 6: Context Switches

What is a context switch? Briefly describe what the OS does during a context switch. Is context switch a desirable thing if our goal is to increase the throughput of the system?

Instructor Solution

A context switch is the procedure the OS kernel uses to stop one process and start (or resume) another on the same CPU. During the switch, the OS must save the state of the currently running process (registers, program counter, and stack pointer) into its Process Control Block (PCB) and then load the saved state of the next process from its respective PCB into the CPU hardware.

From a throughput perspective, context switching is NOT desirable because it is pure “overhead.” During a switch, the CPU is performing administrative tasks for the OS rather than executing user instructions, and it often leads to cache misses as the new process populates the L1/L2 caches with its own data.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Context Switch: The Cost of Multitasking

A context switch is the moment the OS pauses one process and resumes another on the same CPU. It’s the mechanism that makes multitasking possible, but it’s also expensive.

The Context Switch Sequence

Step 1: Timer Interrupt

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Process A running │

│ PC = 0x8048500 │

│ R1 = 42, R2 = 100 │

│ SP = 0xBFFF0000 │

└──────────────────────────────┘

↓ (Interrupt!)

Step 2: Save Process A's State

OS saves to PCB_A:

PC = 0x8048500

R1 = 42, R2 = 100

SP = 0xBFFF0000

(all 32+ registers)

↓

Step 3: Load Process B's State

OS loads from PCB_B:

PC = 0x8048800

R1 = 99, R2 = 50

SP = 0xCFFF0000

↓

Step 4: Resume Process B

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Process B running │

│ Resumes exactly where it left│

│ off from last context switch │

└──────────────────────────────┘

What Gets Saved?

Everything the CPU needs to resume:

// All CPU registers

PC (Program Counter) // What instruction to execute next

SP (Stack Pointer) // Where the stack ends

BP (Base Pointer) // Stack frame base

R0-R15 (General registers) // Intermediate values in computation

FLAGS // CPU condition flags

// Example: Imagine Process A was doing:

int sum = 0;

sum += 10; // Just finished this, R1 = 10

sum += 20; // About to execute this

// PC = address of next instruction

// R1 = 10 (intermediate result)

// Context switch happens HERE

// OS saves: PC (at next instruction), R1=10, etc.

//

// When Process A resumes later:

// PC restores to the right instruction

// R1 = 10 (still has the value)

// Execution continues perfectly!Why It's Expensive: The Overhead

1. CPU Cycles Lost:

Time (nanoseconds):

0-5: Context switch instruction executes

5-10: Register saves

10-20: Memory writes (slow!)

20-25: Load new process registers

25-30: CPU pipeline flushes

30-100: New process starts executing USEFUL code

CPU wastes 30% of time on context switch overhead!

2. Cache Misses (The Real Killer):

Before Context Switch:

L1 Cache (hot):

Process A's data in cache

Very fast access (1-2 CPU cycles)

After Context Switch to Process B:

L1 Cache (stale):

Process A's data still there

Process B needs its own data

CACHE MISS! (must fetch from RAM)

RAM access: 200-300 CPU cycles

vs L1 cache: 1-2 CPU cycles

Impact: 100-300x slowdown for each cache miss!

3. TLB Flush (Translation Lookaside Buffer):

Modern CPUs use a TLB to cache virtual→physical address translations.

// Process A: Virtual 0x1000 → Physical 0x5000

TLB_A[0x1000] = 0x5000

// Context switch to Process B:

TLB must be cleared (or flushed)

Because Process B's virtual 0x1000 might be Physical 0x7000

// Process B: Virtual 0x1000 → Physical 0x7000

TLB_B[0x1000] = 0x7000

// Without flushing: Process B would get Process A's physical address!

// Result: Memory corruption or security breachFlushing TLB costs: 100+ CPU cycles per access until TLB repopulates.

Desirability: The Trade-off

Is context switching desirable for throughput?

Answer: NO, but YES for responsiveness.

Throughput Perspective (Bad):

Theoretical throughput: 1 process, no context switches

├─ Process A uses 100% CPU

└─ Gets MORE DONE per second

Actual throughput: 4 processes with context switching

├─ Process A: 25% CPU - 5% lost to context switches = 20% useful

├─ Process B: 25% CPU - 5% lost to context switches = 20% useful

├─ Process C: 25% CPU - 5% lost to context switches = 20% useful

├─ Process D: 25% CPU - 5% lost to context switches = 20% useful

└─ Total useful work: 80% vs 100% (16% loss from context switches!)

Additional cache misses can reduce effective throughput 30-50%!

Responsiveness Perspective (Good):

Without context switching:

User clicks browser

Waits 30 seconds for video encoder to finish

Browser freezes - BAD

With context switching (100 switches/sec):

Browser gets CPU ~100 times per second

Responds immediately to user input

Video encoder also makes progress

Both feel responsive - GOOD

Real-world consequence:

$ dmesg | grep "context switch"

# Hidden, but happening thousands of times per second

$ vmstat 1

procs -------- Context Switches --------

3456 # 3456 context switches per second

# ≈ 0.3ms wasted per second (small but adds up)Minimizing Context Switches

Modern OSes try to reduce context switches:

// 1. Batch I/O operations

// Keep process running instead of blocking on every I/O

// 2. Use larger time quantums

// Let processes run longer before switching

// Reduces context switches but hurts responsiveness

// 3. NUMA awareness (Non-Uniform Memory Access)

// Keep process on same CPU to preserve cache

// Switching to different CPU = cache flush again!

// 4. CPU affinity

// Bind process to specific CPU core

// Process always runs on same CPU

// Cache stays hotThe Fundamental Trade-off:

| Aspect | More Frequent Switches | Fewer Switches |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Lower (more overhead) | Higher (less overhead) |

| Responsiveness | Better (fair sharing) | Worse (unfair) |

| Latency | Lower (quick response) | Higher (waits long) |

| Fairness | Fair (all get CPU) | Unfair (some starve) |

Modern OSes optimize for responsiveness and fairness, accepting some throughput loss.

Problem 7: Process Dispatch

What’s meant by process dispatch? Briefly explain.

Instructor Solution

Process dispatch is the final stage of the scheduling process where the OS Dispatcher module takes a process from the “Ready” state and gives it actual control of the CPU. This involves: (1) performing a context switch to load the process’s saved state, (2) switching the CPU from Kernel Mode back to User Mode, and (3) jumping to the correct location in the program (using the saved Program Counter) so the process can begin or resume execution.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Process Dispatch: Making the CPU Decision Real

Scheduling vs Dispatch:

Scheduling: DECISION layer

"Which process should run next?"

Runs in kernel mode, makes the choice

Dispatch: EXECUTION layer

"Okay, NOW make it happen!"

Actually loads the process and runs it

Think of it like a kitchen:

Chef (Scheduler): "Next order: Table 5's burger"

Cook (Dispatcher): "Okay, now I'll actually cook it"

Gets all the ingredients (PCB)

Starts the stove (loads CPU state)

The Three Steps of Dispatch

Step 1: Context Switch

Before:

CPU State = Process A (running in user space)

Dispatcher action:

Save Process A → PCB_A

Load Process B ← PCB_B

After:

CPU State = Process B's state (ready to resume)

Step 2: Switch CPU Modes

// Before dispatch:

CPU_MODE = KERNEL_MODE // OS has full access

// Can access memory, I/O, etc.

// During dispatch:

CPU_MODE = USER_MODE // Process has restricted access

// Can't execute privileged instructions

// Can't access memory outside its address spaceWhy this matters:

// In USER_MODE:

*ptr = 0xC0000000; // Try to access kernel memory

// CPU throws: SEGMENTATION FAULT!

// Kernel takes control again

// In KERNEL_MODE (OS code only):

*ptr = 0xC0000000; // Allowed! (kernel can access anything)Step 3: Jump to Program Counter

// Process B was interrupted at address 0x8048ABC

// Its PCB saved:

PCB_B.PC = 0x8048ABC

// Dispatcher action:

CPU.PC = PCB_B.PC; // Load saved PC

jmp *CPU.PC; // Jump to that address

// Process B resumes from where it left off!Without this: Process would start from beginning (main) again - wrong!

Dispatch Happens After Scheduling Decision

Scheduling Policy (Kernel):

"Process B should run next"

Scheduler chooses:

PCB_B (highest priority, longest waiting, etc.)

Dispatcher executes:

1. Save current process A's context

2. Load process B's context

3. Switch to USER_MODE

4. Jump to PCB_B.PC

Result:

Process B running in user space,

using its saved registers,

ready to execute exactly where it paused

Real Example: Timer Interrupt → Dispatch

0ms: Process A running

PC = 0x8048500

Executing: sum += 10;

10ms: TIMER INTERRUPT!

CPU switches to KERNEL_MODE

OS timer interrupt handler runs

11ms: OS scheduler decides:

"Process B should run (it's waited too long)"

Calls dispatcher

11.1ms: Dispatcher executes:

// Step 1: Context switch

Save Process A:

PCB_A.PC = 0x8048501 (next instruction)

PCB_A.R1 = 42 (partial sum)

PCB_A.SP = 0xBFFF0000

...all registers

// Load Process B

Load Process B:

CPU.PC = PCB_B.PC = 0x8048800

CPU.R1 = PCB_B.R1 = 99

CPU.SP = PCB_B.SP = 0xCFFF0000

...all registers

// Step 2: Switch modes

CPU_MODE = USER_MODE

// Step 3: Jump to PC

jmp *CPU.PC; // Jump to 0x8048800

11.2ms: Process B executing!

CPU.PC = 0x8048800 (resuming from saved state)

R1 = 99 (has old values)

Continues as if never interrupted

20ms: Another TIMER INTERRUPT!

Dispatcher switches back to Process A

PC = 0x8048501 (exactly where it left off)

R1 = 42 (still has the value)

What Dispatch Does NOT Do

Doesn’t pick the next process: That’s the scheduler’s job

// Scheduler says: "Process B is next"

// Dispatcher says: "Okay, I'll load Process B"Doesn’t run in user mode: Dispatch is a kernel operation

// Dispatch code runs in KERNEL_MODE

// Only after dispatch completes does CPU switch to USER_MODEDoesn’t create processes: That’s fork()‘s job

// Dispatch just switches between existing processes

// Doesn't create or destroyThe Dispatcher Module

In a real OS, this is typically:

// In Linux kernel (arch/x86/kernel/process.c)

void context_switch(struct rq *rq, struct task_struct *prev,

struct task_struct *next) {

// Step 1: Save prev's registers to prev->thread_info

// Step 2: Load next's registers from next->thread_info

// Step 3: Load page tables (memory management)

// Step 4: Switch to USER_MODE (happens in low-level asm)

}

// This is the actual dispatcher!Summary: Dispatch is the "DO IT" Step

| Step | Done By | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Scheduling | Scheduler | Decide which process is next |

| Dispatch | Dispatcher | Actually make it run on CPU |

| Execution | CPU | Execute the process’s code |

Dispatch is small but critical - it’s the link between scheduling decisions and actual execution.

Problem 8: Voluntary vs Involuntary Context Switches

What is the difference between a “Voluntary” and an “Involuntary” context switch? Give an example of each.

Instructor Solution

A voluntary (cooperative) context switch occurs when a process explicitly yields the CPU (usually by calling a system call to block on I/O or sleep), whereas an involuntary (preemptive) context switch occurs when the OS forcibly interrupts a running process to give the CPU to another process (typically triggered by a timer interrupt or higher-priority event). Voluntary example: a process calls read() and blocks waiting for disk I/O. Involuntary example: a process’s time quantum expires and the timer interrupt forces a context switch.

Elaboration (by LLM):

Two Types of Context Switches

Voluntary (Cooperative): Process says “I’m done for now, switch me out”

Involuntary (Preemptive): OS says “That’s enough, step aside!”

Voluntary (Cooperative) Context Switch

The process willingly gives up the CPU by calling a blocking system call.

// Example: Process reads from disk

int n = read(fd, buffer, 4096);

↓

// read() is a system call

// Process: "I need data from disk, but that's slow"

// Process enters kernel mode

// Kernel: "Okay, I'll block you and switch to another process"

// Context switch happens (but process asked for it!)

// OS: "Wake me when the disk data arrives"

// Process blocks: BLOCKED state (not in Ready queue)

// OS switches to another Ready process

// 100ms later: Disk interrupt! Data arrived!

// OS: "Your data is here, Process A"

// Moves Process A back to Ready queue

// Next scheduled: Process A runs againOther Voluntary Switches:

sleep(5); // "Wake me in 5 seconds"

wait(pid); // "Wake me when child exits"

pthread_cond_wait();// "Wake me when condition is true"Characteristics:

- Process initiates (calls system call)

- Process enters BLOCKED state

- No CPU time wasted (process isn't running)

- Happens naturally during I/O or coordination

- OS can't skip it (must block on I/O anyway)

Why Voluntary?

It’s called “voluntary” because:

Process: "I need X, but it's not ready yet"

"I could spin loop and waste CPU"

"But I'll voluntarily block instead"

OS respects that:

"Good, I'll let you block"

"No forced interruption needed"

Involuntary (Preemptive) Context Switch

The OS forces a context switch, even though the process doesn’t want one.

// Example: Time quantum expires

Process A running:

printf("Hello World");

x = 5;

y = 10;

z = x + y; ← About to execute this

TICK! (10ms timer interrupt)

↓

OS timer handler:

"Time's up! Process A, step aside!"

Process A didn't ask for this!

But OS forces it anyway

Context switch happens:

Save Process A (mid-computation)

Load Process B

Process A is still READY

(not blocked, not waiting)

(just forced to wait its turn)Other Involuntary Triggers:

// 1. Timer interrupt (most common)

TIMER INTERRUPT every 10ms

├─ OS: "Check if anyone else wants CPU"

├─ If yes: force context switch

└─ If no: let current process continue

// 2. Higher priority process becomes ready

Current: Process B running (priority 5)

Event: Process A wakes up (priority 10, higher)

"Higher priority! Context switch!"

// 3. I/O completion (but process wasn't waiting)

Process A running

Disk I/O completes for Process B

OS: "Process B became ready!"

OS: "Process A, step aside for higher priority"Characteristics:

- OS initiates (interrupt, scheduler decision)

- Process remains READY (not blocked)

- Process loses CPU mid-computation

- Happens unexpectedly from process's perspective

- Necessary for fairness and responsiveness

Why Involuntary?

It’s called “involuntary” because:

Process: "I'm using the CPU!"

"I have more work to do!"

OS: "Too bad, I'm taking it anyway"

"You've had your time"

"Other processes need a turn"

(FORCES context switch)

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Voluntary | Involuntary |

|---|---|---|

| Who initiates? | Process (syscall) | OS (interrupt) |

| Process state | BLOCKED → later READY | READY → READY |

| Example | read(), sleep() | Timer, priority |

| Foreseeable? | Yes (process knows) | No (by definition) |

| CPU used? | No (blocked) | Yes (forced switch) |

| Necessity | Required (I/O wait) | For fairness/response |

Real-World Timeline

0ms: Process A: read(fd, buf, 4096);

├─ read() blocks (voluntary)

└─ Process A → BLOCKED state

1ms: Context switch to Process B

Process B running

5ms: Timer interrupt

Involuntary context switch

Process B → READY (still ready, not done)

6ms: Context switch to Process C

Process C running

7ms: Disk completes I/O for Process A

Process A → READY (data arrived!)

8ms: Timer interrupt

Involuntary context switch

Process C → READY

9ms: Context switch to Process A

Process A ready (I/O done, data in buffer)

Resumes read() where it left off

Why Both Are Needed

Without voluntary switches (blocking):

// If process couldn't voluntarily block on read()

int n = read(fd, buffer, 4096);

// Process would spin loop instead:

while (data_not_ready) {

CPU is wasting cycles!

Not doing useful work

Heat, power, no progress

}Without involuntary switches (preemption):

// If OS couldn't force a context switch

while (true) {

computation(); // Never yields

}

Result: One greedy process uses 100% CPU

Other processes starve

No fairness

"Freezing" problems (one process locks others out)Both needed for:

- Fairness: Each process gets CPU time (preemption)

- Efficiency: Don’t waste CPU on I/O wait (voluntary blocking)

- Responsiveness: User interaction responds quickly (preemption)

Voluntary: The process gives up the CPU because it needs to wait for something (e.g., calling read() on a file or sleep()).

Involuntary: The OS forcibly removes the process from the CPU (e.g., the process’s time slice expired, or a higher-priority interrupt arrived).

Problem 9: The First Process in Linux

What’s the name of the “first process” in Linux? What’s its process id? Who creates it?

Instructor Solution

The first process in Linux is named systemd or simply init. It always holds Process ID (PID) 1. This process is created by the Linux Kernel itself during the final stage of the boot sequence after hardware initialization is complete. As the “ancestor” of all other processes, it remains active until the system is shut down, serving as the root of the process tree and managing the startup of all system services and user sessions.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The init Process: Process Tree Root

Every process (except init itself) has a parent. The init process (PID 1) is the ultimate parent of all processes.

Process Tree:

init (PID 1) ← First process created by kernel

├── sshd (SSH server)

│ └── sshd [user session] → login shell → bash

├── getty (terminal)

│ └── login → bash

├── cron (scheduled tasks)

├── syslog (logging)

├── firefox (PID 1234) ← started by user

│ ├── [firefox child threads]

│ └── Subprocess

└── vim (PID 1235) ← started by user

Every process has PPID = 1 or another process.

Why init is Special

Unique property: init is the ONLY process that doesn’t have a parent.

pid_t getppid(void); // Get parent's PID

// For any process except init:

getppid() // Returns PID of parent

// For init:

getppid() // Returns 0 or 1 (special, it has no parent!)Why? Because init is created by the kernel, not by another process.

Boot Sequence: How init is Created

1. BIOS runs

2. Bootloader (GRUB) loads kernel

3. Kernel initializes hardware

├─ Detect CPUs

├─ Setup memory

├─ Detect devices

└─ Load filesystem

4. Kernel creates init process (PID 1)

├─ Loads /sbin/init (or systemd)

├─ Sets PPID = 0 (no parent!)

├─ Assigns PID = 1

└─ Starts execution

5. init starts running

└─ Reads /etc/inittab or /etc/systemd/default.target

└─ Starts system services and daemons

├─ sshd (SSH server)

├─ apache2 (web server)

├─ postgresql (database)

├─ getty (terminal login)

└─ dozens of other services

Result: Fully booted system with all services running

Without init: System would have no services, no login, nothing working!

Role 1: Boot the System (Startup)

Init’s primary role is to start all system services.

$ systemctl list-units --type=service | head -10

UNIT LOADED ACTIVE SUB

apache2.service loaded active running

cron.service loaded active running

ssh.service loaded active running

postgresql.service loaded active runningEach service started by init runs as a separate process with init as parent (PPID=1).

Role 2: Adopt Orphaned Processes

What happens if a child’s parent dies?

// Parent process

pid_t child = fork();

if (child == 0) {

// Child code

printf("Child running");

sleep(100);

} else {

// Parent code

exit(0); // Parent exits while child is still running!

}

// Child: "Hey, my parent died!"

// What happens now?Answer: init adopts the orphan!

Before:

Parent (PID 100) ← Child (PID 101, PPID=100)

Parent exits:

Parent (PID 100) TERMINATED

Child (PID 101) ORPHANED

OS rescues the orphan:

Child (PID 101, PPID=1) ← init adopted it!

init will eventually waitpid(101) to collect its exit status

Why? So the process doesn’t become a zombie permanently.

Role 3: Reap Zombie Processes

A zombie is a process that exited but parent hasn’t called waitpid() yet.

// Careless parent process

pid_t child = fork();

if (child == 0) {

// Child

exit(0); // Child exits

} else {

// Parent

// Never calls waitpid(child)!

sleep(1000);

}

// Child exited but parent didn't wait

Result: Zombie process (PID still allocated, PCB still exists)

If this goes on:

Zombies accumulate

PID table fills up

System can't create new processesSolution: init reaps zombies

If a process never calls waitpid() on its child:

Child exits (zombie)

Parent doesn't waitpid()

↓

Parent dies

Child becomes orphan

↓

init adopts the zombie

init calls waitpid() on ALL children periodically

↓

Zombie cleaned up (PCB released, PID freed)

Modern init: systemd

Modern Linux uses systemd instead of traditional init:

$ cat /proc/1/comm

systemd # systemd is PID 1, not traditional init

$ systemctl status sshd.service

● ssh.service - OpenSSH server daemon

Loaded: loaded (/lib/systemd/system/ssh.service; enabled; vendor preset: enabled)

Active: active (running) since Mon 2024-01-15 10:23:45 UTC; 2 days ago

Main PID: 1234 (sshd)systemd replaces traditional init with:

// Features traditional init didn't have:

- Dependency management (B starts after A)

- Parallel startup (services start simultaneously)

- Automatic restart on failure

- Resource limits per service

- Cgroups (process groups with resource isolation)

- Journal loggingWhat If init Dies? (Never Happens)

If init (PID 1) dies:

├─ All children become parentless

├─ No process to adopt orphans

├─ Zombie processes pile up

├─ System becomes unstable

└─ Usually triggers kernel panic (restart)

In practice:

init is protected by the kernel

If init crashes, kernel panics

Most reliable process in the system

That’s why init is so critical!

Commands to See init

# PID 1 is init (or systemd)

ps aux | grep "^ *root" | head -1

# Shows PID 1 (init/systemd)

# See the process tree

pstree

init

├─ sshd

│ └─ sshd [user]

│ └─ bash

└─ vim

# Every process has init as ancestor

$ cat /proc/12345/status | grep PPid

PPid: 5432 # Parent

$ cat /proc/5432/status | grep PPid

PPid: 1000 # Parent

$ cat /proc/1000/status | grep PPid

PPid: 1 # Eventually reaches init (PID 1)

# Check what process is PID 1

$ cat /proc/1/comm

systemd (or 'init' on older systems)Problem 10: Empty Ready Queue

What does the OS run if the ready queue is empty? Briefly explain.

Instructor Solution

When the ready queue is empty, the OS runs a special process called the Idle Process (or “idle task”). Its primary job is to keep the CPU active and in a known state while waiting for new work to arrive.

Briefly, the idle process often executes a privileged power-saving instruction, such as HLT (Halt) on x86 architectures. This instruction puts the CPU into a low-power state, effectively “turning off” parts of the silicon to reduce heat and battery consumption until the next hardware interrupt (like a timer, a keyboard stroke, arrival of a network packet, etc.) occurs to wake the system back up.

Elaboration (by LLM):

The Idle Task: The CPU's Downtime Process

When all processes are blocked (waiting for I/O, timers, or other resources) and the ready queue is empty, the OS needs something to run. It can’t just do nothing - that would leave the CPU in an undefined state.

What Happens With an Empty Ready Queue?

Bad approach (but conceptually simple):

Ready Queue: [ (empty) ]

Option 1: Do nothing?

├─ CPU is idle but not "off"

├─ CPU still consuming power (full speed, hot!)

└─ Wastes electricity and heat

Option 2: Spin loop?

while (true) { } // Burn CPU cycles doing nothing

├─ Still full power

├─ Generates heat

└─ Wastes electricity

Good approach: Run the Idle Task

Ready Queue: [ (empty) ]

OS checks: "Any processes ready? No!"

OS says: "Run the idle task"

Idle Task:

Loop {

Check for interrupts/new processes

Execute HLT (sleep CPU)

Wake up on interrupt

}

Result:

├─ CPU enters low-power state

├─ Minimal power consumption

├─ Responds immediately to interrupts

└─ No CPU cycles wasted

The Idle Process/Task

Every OS has an idle process (though details vary):

Linux:

$ ps aux | grep idle

root 0 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S 12:00 0:00 migration/0

root 5 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S 12:00 0:10 kworker/0:0

root 7 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S 12:00 0:03 ksoftirqd/0The idle task runs as the lowest priority process (or special kernel task).

Windows:

// System Idle Process (always running when nothing else is)

// PID 0 (system idle)

// Shows in Task Manager when CPU is idleWhat the Idle Task Does

// Simplified idle task pseudocode

void idle_task() {

while (true) {

// Check if any processes became ready

// (probably via interrupt handlers)

if (ready_queue_not_empty) {

// Actually, don't explicitly check

// Interrupts will wake us up

break;

}

// Execute HLT instruction

// CPU enters sleep state

// CPU wakes on interrupt

__asm__("hlt"); // x86 instruction

// Back here when woken by interrupt

// Loop again to check ready queue

}

}The HLT (Halt) Instruction:

HLT ; Halt the processor

; CPU stops executing instructions

; CPU enters low-power state

; Only wakes on hardware interrupt (NMI, APIC, etc.)

; Resumes instruction after HLT when wokenWhy Not Just Spin Loop?

Spin Loop (Wasteful):

void bad_idle_task() {

while (true) {

// Do absolutely nothing

// But keep executing this loop

}

}

CPU state:

- Core: Active, running instructions (the while loop)

- Clock: Full speed

- Power: 100% (or high percentage)

- Heat: Maximum

This wastes significant power on a laptop or server!HLT (Efficient):

void good_idle_task() {

while (true) {

__asm__("hlt"); // Sleep until interrupt

}

}

CPU state:

- Core: Halted, no instructions executing

- Clock: Reduced or stopped

- Power: Minimal (1-5% of active power)

- Heat: Minimal

This saves significant power and reduces cooling needs!Real power difference:

Laptop on AC power (100% CPU idle with spin loop):

Power consumption: 100W

CPU temp: 95°C

Fan: Loud and spinning

Laptop on AC power (100% CPU idle with HLT):

Power consumption: 10W

CPU temp: 45°C

Fan: Off or very quiet

When Idle Task Runs

Scenario 1: Boot time (all processes sleeping)

Boot sequence:

1. init starts

2. Services fork (but block on I/O waiting for devices)

3. No process is ready yet

4. Idle task runs

5. Devices initialize

6. Services wake up

7. Idle task gives up CPU

Scenario 2: User process waiting for I/O

User runs: vim file.txt

vim reads from disk:

├─ Makes read() syscall

├─ Blocks in BLOCKED state

├─ No longer in ready queue

Ready queue now empty!

Idle task runs while disk I/O completes

Disk I/O done:

├─ Interrupt wakes idle task

├─ vim moves to READY queue

├─ Next context switch: run vim

└─ Idle task stops running

Scenario 3: Busy server (idle task almost never runs)

Web server with 100 open connections:

Process 1: Handling request (READY)

Process 2: Waiting for database (BLOCKED)

Process 3: Processing data (READY)

Process 4: Writing response (READY)

Ready queue has processes!

Idle task never (or rarely) runs

CPU always busy with user processes

Idle Task and Power Management

Modern systems use idle states with different power levels:

x86 States (C-States):

C0 (Active): CPU running at full speed (100% power)

C1 (Halt): HLT, minimal power (~80% power)

C1E (Enhanced): Reduce voltage + HLT (~60% power)

C2 (Stop): More aggressive sleep (~40% power)

C3 (Sleep): Deep sleep, loss cache (~20% power)

C6 (Deeper): Even deeper sleep (~5% power)

The idle task can request different C-states depending on power policy:

// If system needs responsiveness:

hlt(); // C1 - wake quickly

// If system can tolerate delay:

acpi_processor_idle(); // C3 or C6 - deeper sleepTrade-off: Deeper sleep = lower power but slower wake-up.

The Idle Task is Still a Process

Even though it’s special:

// It appears in process lists

$ ps aux | grep idle

root 0 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S boot 0:00

// It has a PCB

// It's scheduled like any other process

// Priority: Lowest (so real work always runs first)

// If everyone else is running:

// Idle task never executesIn Linux, it’s often PID 0 or integrated into the scheduler.

Problem 11: System Idle Task

What’s the purpose of the “system idle task” and briefly explain what this task does?

Instructor Solution

The purpose of the system idle task is to provide the CPU with a valid set of instructions to execute when no other runnable processes are available in the system. It ensures the processor never enters an undefined state and allows the Operating System to maintain control during “dead time.”

To perform this, the task typically runs an infinite loop that executes a privileged power-saving instruction, such as HLT (Halt) on x86 architectures. This instruction puts the CPU into a low-power state, effectively “turning off” parts of the silicon to reduce heat and battery consumption until the next hardware interrupt (like a timer, a keyboard stroke, arrival of a network packet, etc.) occurs to wake the system back up.

Elaboration (by LLM):

System Idle Task vs Idle Process

Problem 10 discussed the idle process - what runs when the ready queue is empty.

Problem 11 is asking about the same concept but focusing on the actual code/mechanism.

The terms are often used interchangeably:

- Idle process: The data structure (PCB) managed by OS

- Idle task: The code/instructions that execute

- System idle task: The kernel’s idle functionality

Purpose of the Idle Task

Purpose 1: Ensure CPU never idles

├─ CPU must always have something to execute

├─ Can't leave CPU in undefined state

└─ Idle task provides valid instructions

Purpose 2: Power efficiency

├─ Reduce power consumption when no work

├─ Save battery on mobile devices

├─ Reduce data center cooling costs

└─ HLT puts CPU into low-power C-state

Purpose 3: Maintain OS control

├─ OS continues running even when idle

├─ Can respond to interrupts immediately

├─ Can wake up when work arrives

└─ Never truly hands over control to BIOS

What the Idle Task Does

void idle_task_main() {

// The idle task runs in a loop

// when no other process is ready

while (true) {

// Optional: Check power state

// Optional: Prepare for deeper sleep

// Execute HLT (or equivalent)

__asm__("hlt"); // x86 instruction

// HLT puts CPU in low-power state

// CPU only wakes on interrupt

// When woken:

// - Check if any process became ready

// - Continue loop (HLT again if nothing ready)

// - Or context switch if ready process waiting

}

}HLT Behavior:

Before HLT:

├─ CPU running at full frequency

├─ Power: ~100 watts

└─ Heat: Significant

HLT executes:

├─ CPU frequency drops

├─ Voltage reduced

├─ Power: ~10 watts (order of magnitude less)

└─ CPU "sleeps"

Interrupt arrives (timer, disk, network):

├─ CPU wakes immediately

├─ Resumes next instruction after HLT

├─ No state lost (registers preserved)

└─ Responds to interrupt

Infinite Loop with HLT

// This is what the idle task essentially does:

void idle_task() {

// This loop runs forever until system shutdown

while (true) {

// Infinite loop

hlt(); // Sleep until interrupt

// When woken: loop again

}

}

// The OS scheduler will:

// 1. If ready queue has processes: switch to them (don't run idle task)

// 2. If ready queue empty: run idle task

// 3. Idle task executes HLT

// 4. CPU sleeps

// 5. Interrupt wakes CPU

// 6. Scheduler checks again: is there a ready process?

// 7. If no: go back to step 3

// 8. If yes: context switch to ready processWhy Not Just Spin Loop?

// Bad approach:

void bad_idle_task() {

while (true) {

// Do nothing

// But keep looping

// CPU stays at full power (wastes energy!)

}

}

// Good approach:

void good_idle_task() {

while (true) {

hlt(); // Sleep, save power

}

}

Energy difference on a laptop:

Spin loop: 100W × 1 hour = 100 Wh

HLT loop: 10W × 1 hour = 10 Wh

Savings: 90W per hour idle!

On a server: 90W × 24h = 2160 Wh/day

Annual: ~790 kWh saved per idle core!The Cycle

Ready Queue: [ProcessA, ProcessB]

Scheduler: Run ProcessA

ProcessA uses time quantum

Scheduler: Run ProcessB

ProcessB calls read() (blocks)

ProcessB moves to BLOCKED queue

Ready Queue: []

Scheduler: No ready process!

Run idle task

Idle task executes HLT

CPU sleeps...

(Time passes)

Disk I/O completes

Interrupt wakes CPU

ProcessB moves back to ready queue

Ready Queue: [ProcessB]

Scheduler: Run ProcessB

Idle task stops running

System Idle Task vs "Spinner" Task

Some older systems used a busy-wait “idle” process:

// Old, inefficient approach:

void spinner_idle() {

volatile int i = 0;

while (true) {

i++; // Do absolutely nothing meaningful

// But keep the CPU busy

}

}

// Modern approach (all systems now):

void hlt_idle() {

while (true) {

__asm__("hlt"); // Put CPU to sleep

}

}Modern CPUs ALL use HLT or equivalent because:

- Power consumption too important

- Thermal limits in chips

- Data center power budgets

- Mobile device battery life

The idle task is considered one of the most important OS components for power efficiency!

Problem 12: System Call Failure Conditions

For each of the following system calls, give a condition that causes it to fail: fork, exec, chdir, read.

Instructor Solution

fork: Fails if the system-wide limit on the number of processes has been reached or if the system is out of physical memory.

exec: Fails if the specified file does not have execute permissions or if the file does not exist.

chdir: Fails if the target path is not a directory, does not exist or if the process lacks permission to search the intended path.

read: Fails if the file descriptor is invalid (e.g., not open) or if the underlying hardware encounters a physical I/O error.

Elaboration (by LLM):

When System Calls Fail: Error Conditions

System calls fail when the OS can’t fulfill the request. Each failure has specific conditions.

fork() - Create a New Process

Condition 1: Resource limit reached

// Each process has resource limits

// Check current limits:

$ getrlimit(RLIMIT_NPROC, &rlim);

// Example: Max processes per user = 1024

if (current_processes >= 1024) {

// fork() fails with EAGAIN

// errno = EAGAIN (resource temporarily unavailable)

}Condition 2: Out of memory

// fork() needs to allocate:

// - New PCB (small, ~4KB)

// - New page tables (~4KB)

// - New stack (~8MB)

// - Potentially copy entire address space

if (available_memory < required_memory) {

// fork() fails with ENOMEM

// errno = ENOMEM (out of memory)

}Example: Creating 10,000 forks exhausts memory:

$ cat fork_bomb.c

int main() {

while (1) fork(); // Creates processes exponentially

}

$ gcc -o fork_bomb fork_bomb.c

$ ./fork_bomb

[System slows to crawl]

[fork() starts failing with EAGAIN]

[Eventually hits hard memory limit]exec() - Replace Process Image

Condition 1: File doesn’t exist

execve("/nonexistent/binary", argv, envp);

// errno = ENOENT (no such file or directory)Condition 2: No execute permission

$ touch no_execute.txt

$ chmod 644 no_execute.txt // Remove execute bit

$ gcc -o binary binary.c

execve("./no_execute.txt", argv, envp);

// errno = EACCES (permission denied)

execve("./binary", argv, envp); // OK, has execute bitCondition 3: Not a valid executable

execve("/etc/passwd", argv, envp); // Text file, not executable

// errno = ENOEXEC (exec format error)Condition 4: No execute permission for parent directory

$ chmod 000 /some/dir/

$ execve("/some/dir/binary", argv, envp);

// errno = EACCES (can't search directory)chdir() - Change Working Directory

Condition 1: Path is not a directory

$ chdir("/etc/passwd"); // passwd is a FILE, not directory

// errno = ENOTDIR (not a directory)Condition 2: Directory doesn’t exist

chdir("/nonexistent/path");

// errno = ENOENT (no such file)Condition 3: No permission to search the directory

$ mkdir -p /restricted

$ chmod 000 /restricted // Remove all permissions

$ chdir("/restricted");

// errno = EACCES (permission denied)Condition 4: Path component doesn’t exist

chdir("/home/user/documents/nonexistent/folder");

// Fails at "nonexistent" (first nonexistent component)

// errno = ENOENTread() - Read from File Descriptor

Condition 1: Invalid file descriptor

int fd = 999; // Not open!

char buf[100];

read(fd, buf, 100);

// errno = EBADF (bad file descriptor)Condition 2: File descriptor was closed

int fd = open("/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY);

close(fd);

read(fd, buf, 100); // fd is now invalid!

// errno = EBADFCondition 3: File descriptor opened for writing, not reading

int fd = open("/tmp/file", O_WRONLY); // Write only

read(fd, buf, 100);

// errno = EBADF (or EINVAL depending on OS)Condition 4: I/O error (hardware failure)

// Disk read error occurs:

// - Bad disk sector

// - Disk disconnected during read

// - Network device offline

read(fd, buf, 100);

// errno = EIO (input/output error)Condition 5: Reading from non-readable device

int fd = open("/dev/null", O_WRONLY); // Write only device

read(fd, buf, 100);

// errno = EBADF or EINVALSummary Table

| System Call | Failure Condition | Error Code |

|---|---|---|

| fork | Process limit exceeded | EAGAIN |

| fork | Out of memory | ENOMEM |

| exec | File doesn’t exist | ENOENT |

| exec | No execute permission | EACCES |

| exec | Not a valid executable | ENOEXEC |

| chdir | Path is not a directory | ENOTDIR |

| chdir | Directory doesn’t exist | ENOENT |

| chdir | No permission to search | EACCES |

| read | Invalid file descriptor | EBADF |

| read | File descriptor closed | EBADF |

| read | Not opened for reading | EBADF |

| read | Hardware I/O error | EIO |

Error Handling Pattern

All system calls return errors consistently:

// Pattern 1: Most system calls return -1 on error

int result = fork();

if (result == -1) {

perror("fork"); // Prints: "fork: Error message"

exit(1);

}

// Pattern 2: Check errno for details

ssize_t n = read(fd, buf, 100);

if (n == -1) {

if (errno == EBADF) {

printf("Bad file descriptor\n");

} else if (errno == EIO) {

printf("I/O error\n");

}

}

// Pattern 3: Use strerror() for friendly message

if (chdir("/path") == -1) {

printf("chdir failed: %s\n", strerror(errno));

}Real-World Errors

$ cat fork_test.c

int main() {

if (fork() == -1) {

perror("fork");

return 1;

}

}

$ gcc -o fork_test fork_test.c

$ ./fork_test

$ echo $?

0 # Success

$ cat exec_test.c

int main() {

if (execve("/nonexistent", NULL, NULL) == -1) {

perror("execve");

}

}

$ gcc -o exec_test exec_test.c

$ ./exec_test

execve: No such file or directory

$ cat chdir_test.c

int main() {

if (chdir("/nonexistent") == -1) {

perror("chdir");

}

}

$ gcc -o chdir_test chdir_test.c

$ ./chdir_test

chdir: No such file or directoryProblem 13: fork vs exec

What is the difference between fork and exec system calls in Linux?

Instructor Solution

The fundamental difference lies in whether you are creating a new process or replacing the current program.

- fork(): Creates a new child process that is an exact duplicate of the parent. After the call, two processes exist, both running the same code and sharing the same state (registers, variables, and open files).

- exec(): Replaces the entire current process image (code, data, heap, and stack) with a new program from a file. It does not create a new process; instead, the existing process “transforms” into one that executes the instructions of the program that is loaded while keeping the same Process ID (PID).

Elaboration (by LLM):

fork() vs exec(): Two Different Operations

These are fundamentally different operations often used together but serving different purposes.

fork() - Duplicate the Process

What fork does:

pid_t child_pid = fork();

// After fork() returns:

// - TWO processes exist (parent + child)

// - Both are running the SAME program

// - Both have the SAME code and data

// - Both have separate memory (copy-on-write)In memory after fork():

Before fork():

Process A

├─ PID = 1000

├─ Code: main(), foo(), bar()

├─ Data: x=5, y=10

└─ Registers: PC=0x8048500, ...

fork() executes:

After fork():

Process A (Parent)

├─ PID = 1000 (unchanged)

├─ Code: main(), foo(), bar()

├─ Data: x=5, y=10

├─ Registers: PC=0x8048500, ...

└─ fork() returns: 1001 (child's PID)

Process B (Child)

├─ PID = 1001 (new!)

├─ Code: main(), foo(), bar() (COPY)

├─ Data: x=5, y=10 (COPY)

├─ Registers: PC=0x8048500, ... (COPY)

└─ fork() returns: 0 (marker for child)

Key point: Both processes are running the SAME program!

exec() - Replace the Program

What exec does:

execve("/bin/ls", argv, envp);

// After exec() returns:

// - ONE process exists (the original one)

// - It's now running a DIFFERENT program (/bin/ls)

// - The original code is GONE

// - Same PID (process identity unchanged)In memory after exec():

Before exec():

Process A

├─ PID = 1000 (unchanged)

├─ Code: main(), foo(), bar()

├─ Data: x=5, y=10

└─ Registers: PC=0x8048500, ...

execve("/bin/ls", ...) executes:

After exec():

Process A (TRANSFORMED)

├─ PID = 1000 (SAME!)

├─ Code: ls program (/bin/ls)

├─ Data: ls's variables

├─ Registers: PC=0x8048400 (ls's main), ... (reset)

└─ NO RETURN (new program runs)

Key point: Same process, different program!

Usage Pattern: The Shell

The shell uses both together:

$ ls -laWhat the shell does:

pid_t child = fork(); // Create child process

if (child == 0) {

// Child process

execve("/bin/ls", argv, envp); // Replace with ls program

// Child no longer exists as shell!

// Now runs ls's code

}

else {

// Parent process (the shell)

wait(child); // Wait for child to finish

// Print prompt again

}Timeline:

Time 0: Shell running (PID 100)

User types: ls -la

Time 1: Shell calls fork()

Child (PID 101) created, copies of shell code

Time 2: Child calls execve("/bin/ls", ...)

Child's memory: shell code REPLACED with ls code

Child now runs ls (still PID 101)

Time 3: ls program executes

Shows directory listing

Time 4: ls finishes, exits

Child (PID 101) terminates

Time 5: Shell wakes from wait()

Prints command prompt again

Ready for next command

fork() Does NOT Create a New Program

// Example of fork() ALONE (without exec):

int main() {

printf("Before fork\n");

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

printf("Child process\n");

// Child also runs main(), foo(), bar()

// Not running a different program

} else {

printf("Parent process\n");

wait(pid);

}

return 0;

}

Output:

Before fork

Child process

Parent process

// Both processes ran the SAME program (this one)!If you just fork(), both run the same binary.

exec() Does NOT Create a New Process

// Example of exec() alone:

int main() {

printf("Running /bin/ls\n");

execve("/bin/ls", argv, envp);

// This line never executes!

printf("After exec\n"); // ← Never printed

}

Result:

Running /bin/ls

[ls output: directory listing]

// Only ONE process!

// The execve() REPLACED the running processThe “After exec” line never runs because the process transformed.

fork() + exec() Together

This is the most common pattern:

pid_t child = fork();

if (child == 0) {

// Child process

// Now run a different program

execve("/bin/ls", argv, envp);

// If exec fails:

perror("execve");

exit(1);

} else {

// Parent process

// Still running original program

wait(child);

}Why fork() THEN exec()?

Reason: We need TWO PROCESSES

- Child: runs the new program

- Parent: continues running the shell

If we exec() without fork():

Parent (shell) would be REPLACED

Shell would DISAPPEAR

User would lose shell prompt!

So we:

1. fork() to create child

2. exec() in child (child replaces, parent stays)

3. wait() in parent (wait for child to finish)

4. Shell continues (parent unaffected)

Comparison Table

| Aspect | fork() | exec() |

|---|---|---|

| Processes | Creates 2 (parent + child) | Uses existing process |

| PID | Child gets new PID | PID unchanged |

| Return | Returns twice (child gets 0) | Doesn’t return (replaces) |

| Program | Both run SAME program | Replaces with new one |

| Memory | Child memory is copy | Old memory DISCARDED |

| Usefulness | For multitasking | For running new program |